Art

Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers

The National Gallery, London

5/5

Van Gogh in Provence

Blockbuster exhibitions are difficult to appreciate and put into context. Van Gogh’s paintings, motifs and style are so ubiquitous that it becomes challenging to see his work afresh, particularly when squeezed in a crowd of eager visitors without having sufficient space or time to give the paintings their due consideration. Matters are not helped by the misleading and frankly stupid exhibition title, “Poets and Lovers” which does not relate to the exhibition content and appears to have been put through the clickbait creation algorithm. Nevertheless, none of these considerable efforts succeed in supressing the vibrant presence of Van Gogh’s genius.

Van Gogh was definitely one of a kind. If we discard for a moment his celebrity status and everything that it entails, his artistic authenticity has not dated and moves us as much as always. Contrary to the exhibition title, what is on show are mostly landscapes, with a few portraits, townscapes and interiors, from the last few years of his life spent in Provence, in Arles and Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. His best-known works date from this period of artistic maturity, strongly influenced by the light and beauty of Provence. National Gallery curators have secured a large number of loans from many collections worldwide, some of which are rarely seen. It was with delight that I recognised Provençal landscapes and light in Van Gogh’s colouristic and compositional schemes: gardens, olive trees, plane trees, sunflowers, rocky landscapes of the Alpilles.

A few of the more famous of Van Gogh’s paintings genuinely impress. The glorious Rhône makes an appearance in the famous Starry night over the Rhône (La Nuit étoilée, 1888) from Musée d’Orsay which is so much more striking than in reproduction. More subtle than its famous counterpart, the Starry night from MoMA, it draws the viewer into the painter’s field of vision. Using a palette of blues and yellows Van Gogh finds an original way to express the feeling of being enveloped in a warm blue night sky scattered with stars on the banks of the Rhône. A couple on the bottom edge reflect the wonder by looking up at the painter.

The Sunflowers (1889) from the Philadelphia Museum surpass the earlier version from the National Gallery. The colour composition is compelling and feels complete. The flat light blue-green background, also used in his stunning self-portrait at Harvard, adds the needed contrast to the flowers and results in mesmerising luminosity.

Another objection I have to the National Gallery’s curation, aside from their tenuous thematic grouping, is that they have removed the painting techniques from the labels next to the works. This seems to be a modern trend I have seen elsewhere which I find unhelpful and superficial to say the least. If education is in part a purpose of the National Gallery, how does providing less information assist in fulfilling it? Those not interested can simply disregard it or don their audio guides which thankfully keep them quiet.

The Monmajour drawings are an excellent addition to the exhibition as they show Van Gogh’s draughtsmanship and versatility, and the way he constructed his compositions. They also provide a contrast to his colourful canvases.

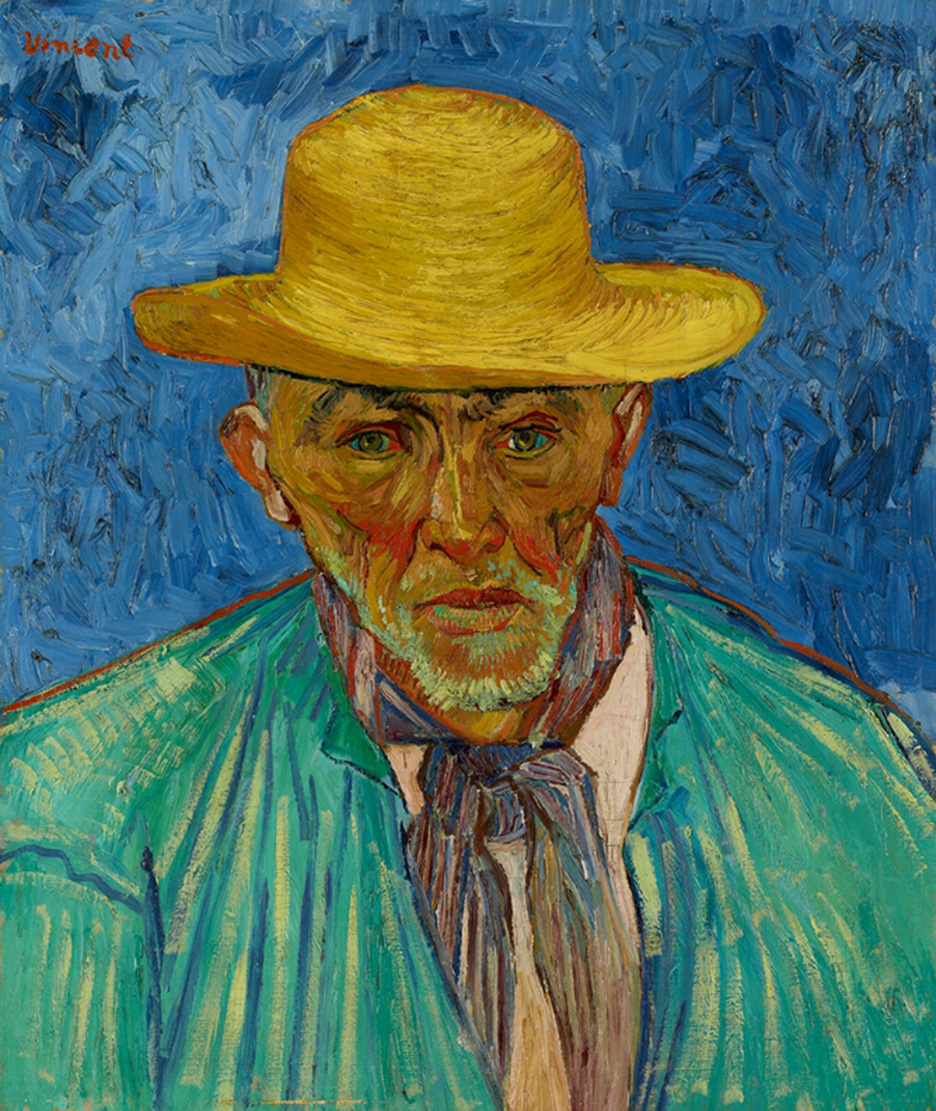

Van Gogh developed a recognisable and arresting style in portraiture. One of the most exciting portraits in the exhibition is Portrait of the Peasant (Patience Escalier) from 1888. The man’s name means ‘patient staircase’ and there is something of this in his resigned expression. And yet in contrast the portrait is also intensely colourful, foreshadowing the fauvists and the expressionists.

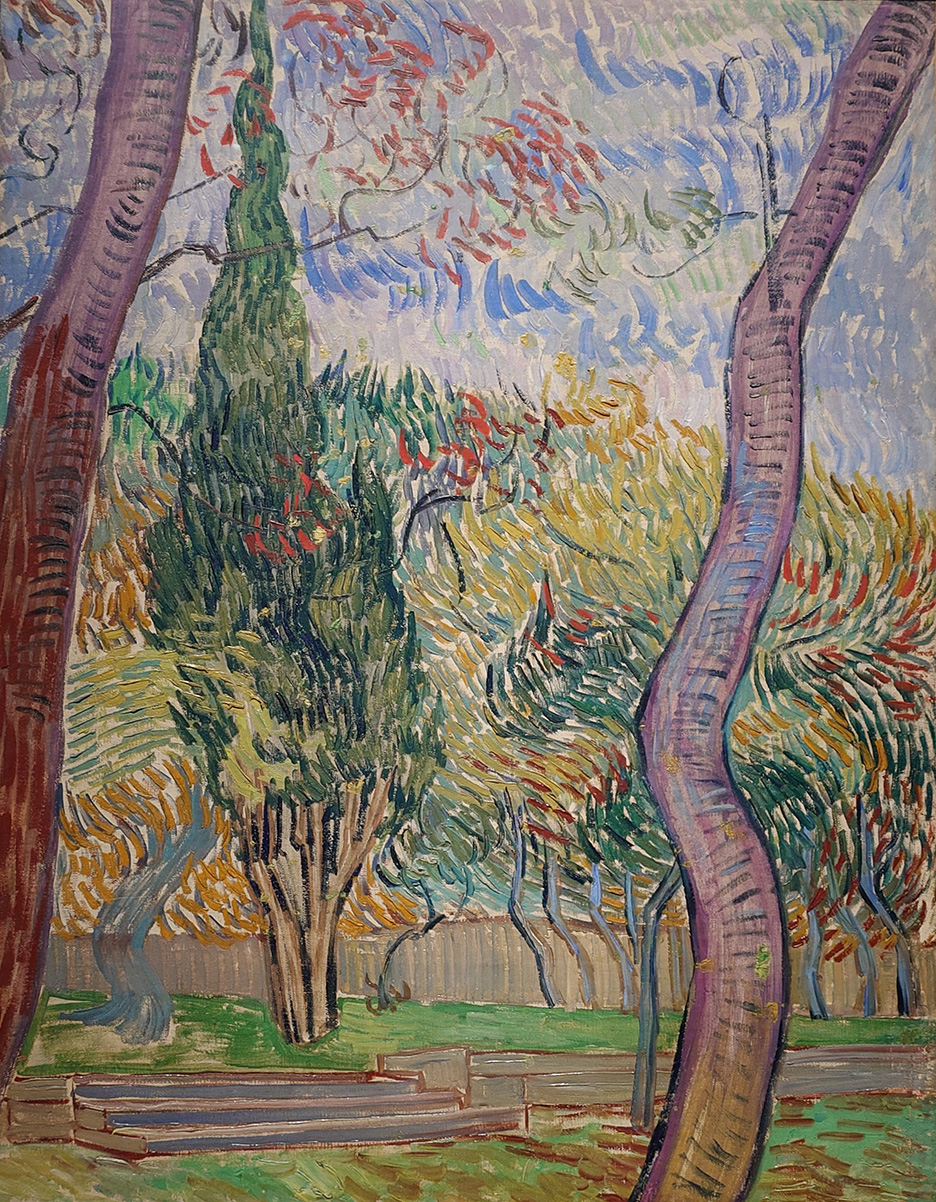

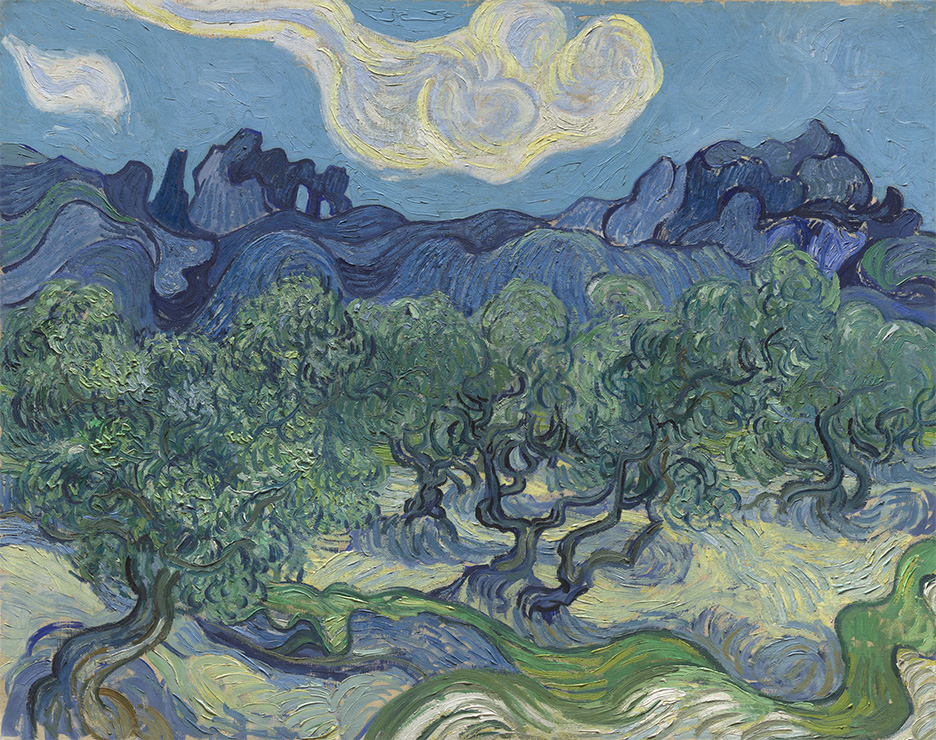

There is a stunning image of olive trees with a background of blue mountains and characteristic swirly clouds from MoMA (The Olive Trees, 1889). In another beautiful canvas, the yellow building of the Hospital at St Rémy (1989) is dwarfed by the tall trees reaching into the clear blue sky. And perhaps one of my favourites is the Trees in the Garden of the Asylum (also 1889, from a private collection), built from colourful curved lines to represent the foliage and sky. Its composition is also beautiful with the two tree trunks randomly dissecting the view, but adding just the right amount of tension to the arrangement, obstructing the eye the better to focus it on the magnificent background.

Beyond celebrity, celebrity by suicide, and the facile myths of the tortured artist, we should attempt to see the singular artistic vision of Van Gogh who in the last years of his life provided us with a rich treasure-trove of beautiful and exciting works which will be observed and enjoyed for years to come.