Art

Radical Harmony: Helene Kröller-Müller’s Neo-Impressionists

The National Gallery, London

4/5

Original colour textures

Neo-impressionism or postimpressionism is easy to overlook as an offshoot of the much more popular impressionism but was in fact radical in many ways and clearly led the way to modern art as this exhibition reveals. We are treated to examples from a large collection assembled by Helene Kröller-Müller, usually displayed at her museum in Otterlo in the Netherlands, and they get more visually arresting as you engage with the characteristics of the style and move through the rooms. The main proponents were Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, but the exhibition includes interesting works by many other artists, most notably the multi-talented Henry van de Velde.

The most salient feature of the neo-impressionist style was the new treatment of colour, divisionism, where pure dots of colour are painted side-by-side for the eye to interpret them as a mix, creating unusual tonalities, perceptions and vibrations. There is this intriguing colour combination or shall I say dot combination that results in a kind of purple, a colour that denotes a shadow of objects and beings, cold and yet also warm, translucent, but also solid. Van de Welde uses it for shadows, particularly at dusk, Théo van Rysselberghe for evanescent smoke textures. Together with other colouristic solutions it brings a fresh sense of originality to these works.

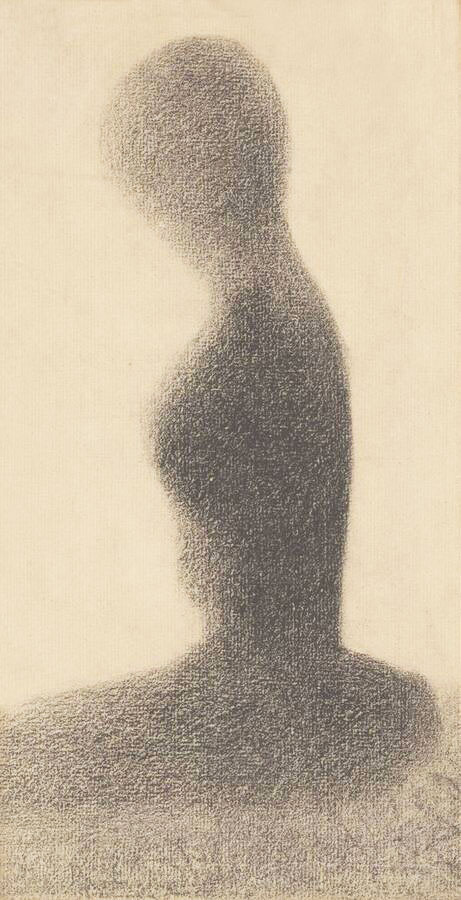

The most interesting discovery are Seurat’s conté crayon drawings, such as Woman with a muff (c.1884) and Young woman: study for a ‘Sunday on la Grande Jatte’ (1884-5). Nothing like his paintings, their unusual textures and simplicity of composition make them look more like modern mezzotints. Seurat’s little gem of a study for La Grande Jatte from 1984-5 owned by the National Gallery was a pleasure to look at. I don’t remember noticing it previously in the main gallery. Perhaps I even prefer this study to the final painting, a fully finished little canvas, but its ambition restrained, like looking through a keyhole at a perfectly staged waterside composition.

Jan Toorop whom I mostly know as the famous father of the great painter Charley Toorop, was in fact a much bigger star in his own time than his daughter ever was. He shows impressive versatility across his work, light and delicate landscapes, slightly sentimental but powerful works of social commentary, intricate portraits.

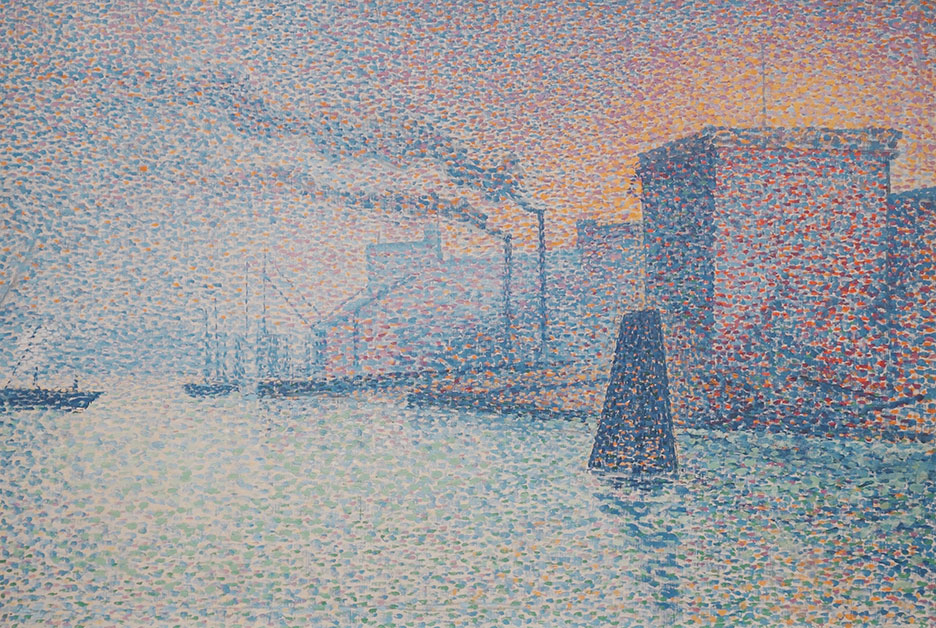

There are a couple of paintings of the Thames in London: Toorop’s Bridge in London (Charing Cross), c.1888-9, and Georges Lemmen’s Factories on the Thames, c. 1892. While Toorop’s canvas is light, gentle and radiant, Lemmen’s appears like a deconstruction of Monet’s views of the sunset on Thames which were in fact created much later. The simple and vibrant colour solutions resonate with my frequent encounters with the same view.

On a more mundane note, you can only bring a very very small bag into the exhibition, which means you have no choice but to leave your stuff in the cloakroom for £3 per item. The cloakroom is in such a location that a huge queue which inevitably forms prevents the flow of the people to the exhibition. It is so oversubscribed that you need to wait quite a while in a tight formation next to the equally long queue for the toilets to leave and recuperate your stuff. A tidy way to get extra income National Gallery, but please let’s have some lockers, so at least we don’t have to spoil our enjoyment of great art by waiting forever with tourists jumping the queue.

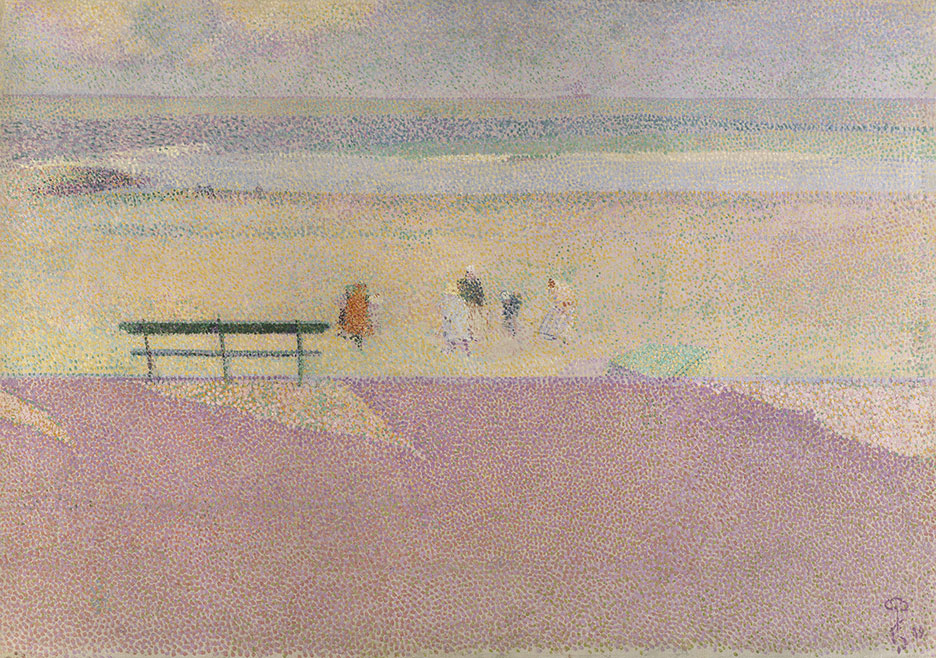

Théo van Rysselberghe, although undoubtedly a great painter, was more conventional in his approach, although his landscapes, portraits and group scenes have well-crafted compositions and a captivating meditative mood. But it is his pared down seascape Coastal Scene (c. 1892) owned by the National Gallery, celebrating a bright sunny view of the Mediterranean from the French coast, that appeals the most.

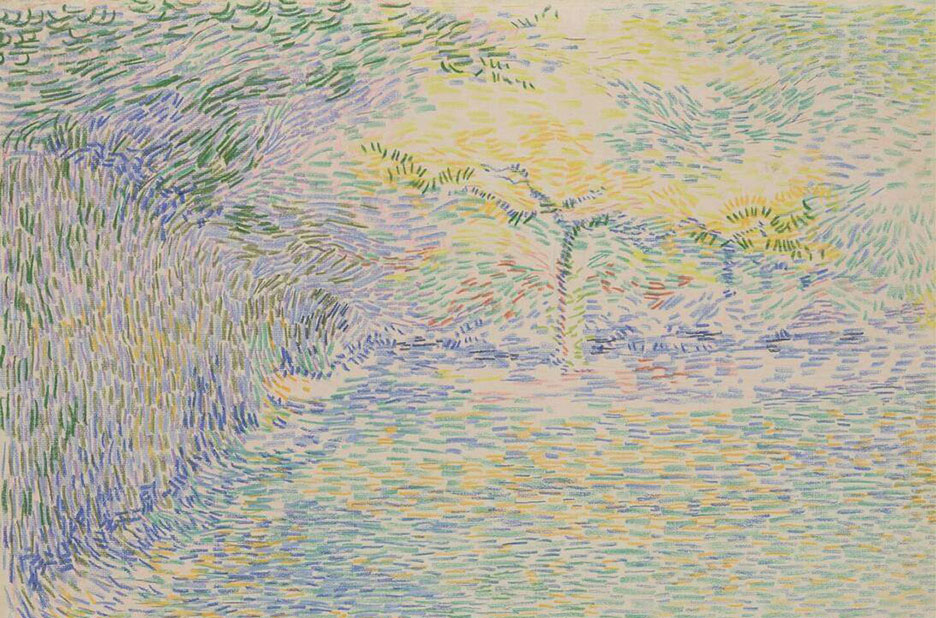

The picturesquely named Johan Thorn Prikker is represented by three drawings of undulating colour lines which the artist called his ‘sun moments’. They clearly echo Van Gogh as much as Toorop’s landscapes do. Simple and effective, they showcase the more abstract direction taken by the neo-impressionist sensibility in the 20th century.

However, it is Henry van de Velde that impresses the most with Twilight (1889), Woman reading (c. 1891), and his almost abstract landscape Seashore (Beach at Blankenberghe), 1889. Amazingly these are all youthful works before he grew disillusioned with the cold application of pointillist techniques and decided to concentrate on architecture and design.