Art

The Shape of Things: Still Life in Britain

Pallant House Gallery, Chichester

4/5

About objects and time

Pallant House Gallery punches above its weight again in this excellent overview of Still Life in British art. This large exhibition features about 150 works representing 100 artists from the 17th century onwards, although the majority are from the 20th century. As the scope is stretched wide, it allows for a great variety resulting in both interesting discoveries of lesser-known art and poorer representation of better-known artists with less salient or successful examples. Masters of the still life genre stand out, such as Ben Nicholson, his father William Nicholson and William Scott. There are also individual masterpieces by John Craxton, Dod Proctor, Nina Hamnett and Edmund de Waal and some interesting discoveries to be made, in my case Tristram Hillier and Rodrigo Moynihan.

I will chart my impressions chronologically even though the exhibition follows a thematic format, with mixed success.

It’s great to see Pallant include an early still life by a Chichester artist from 18th century. Still-Life with joint of beef on a pewter dish by George Smith (c.1750-60) shows off a large dark hunk of meat on a white tablecloth and black background contrasted with textures of other items on the table. It would not be out of place in a Spanish art gallery next to a Goya’s still life.

Mary Moser’s Summer Flowers on a Ledge (1768) is delightful and should have really been part of the current exhibition at Tate Britain Now You See Us: Women Artists in Britain 1520–1920. It’s delicate and accomplished and has a certain satisfying lightness. Mary Moser is such as important figure as one of only two female founding members of the Royal Academy, and yet it is very rare that we see any of her art today.

Nina Hamnett’s compositions always captivate, such as the harmonious Still life (Blue stove) from c. 1915., presenting us with a slightly angular non-sentimental vision infused with soft earthy colours.

William Nicholson’s striking The Silver Casket and Red Leather Box from 1920 stands out beautifully from the dark blue wall and shows off its powerful colour combinations. Small in size, it plays with objects of status with skilled humility.

The only paining by Dod Procter I have ever seen in real life is the famous Morning, so I was pleased to see another great work displayed here, Black and White from 1932. The gorgeous soft textures of different materials such as ermine, silk, leather, upholstery, glass, are enhanced with a use of a reduced palette of colours. The colour space is similar to Morning, largely sourced from white and with a delicate warmth.

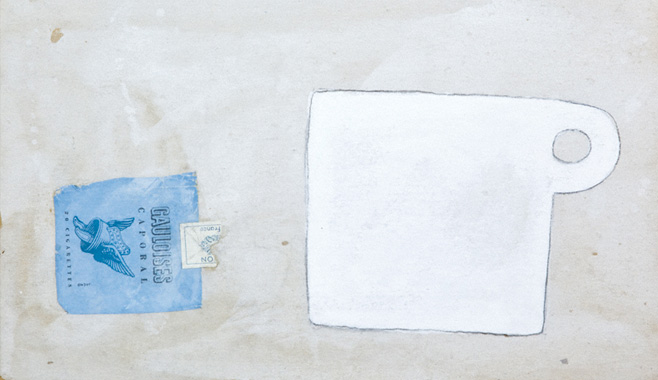

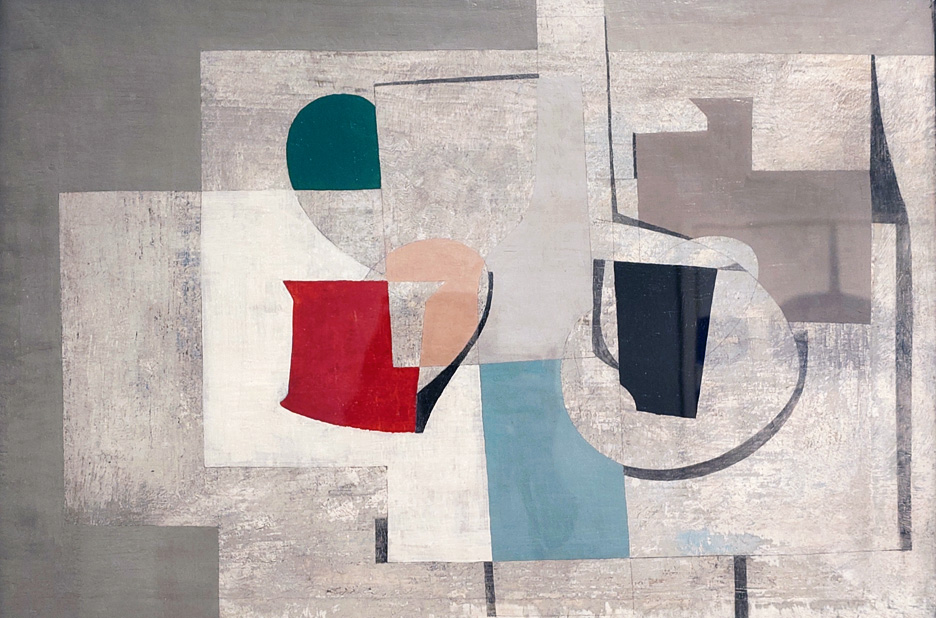

The heart of the exhibition is indeed in the decades from 30s to 50s when the genre came to a new prominence in the darker times of scarcity and newly found simplicity. One of the most impressive paintings of the exhibition, Ben Nicholson’s Still Life from 1934 shows his departure towards abstraction. We can partially recognise two cups and a jug which have been flattened and yet are subject to light refractions of a 3D reality. I love the way Nicholson combines flat colour, seemingly randomly chosen, with the soft grey washed background, it shouldn’t work colouristicly, but it does. This painting was part of the Pallant’s Nicholson exhibition in 2021 which showcased some excellent still lives. William Scott’s Cup from 1974 is for me one of the most wonderous works in this exhibition. Scott has a way of painting flatness that makes it poetic and orderly and yet somehow intimate.

John Craxton’s Hare on a Table from 1944-46 which often hangs in Pallant’s permanent collection is a great example how a clinical and macabre subject can be made universal and infused with resonance. The hare is beautiful and yet dead. We pity his demise but admire the painting of it. Aren’t we a piece of work? Not surprising that Craxton was socialising with Lucian Freud at this time, who has also given us many unflinching representations of uncomfortable or morbid realities. As mentioned in the excellent Craxton exhibition at the Pallant Gallery earlier this year, in the grim war years Craxton and Freud found dead animals to paint.

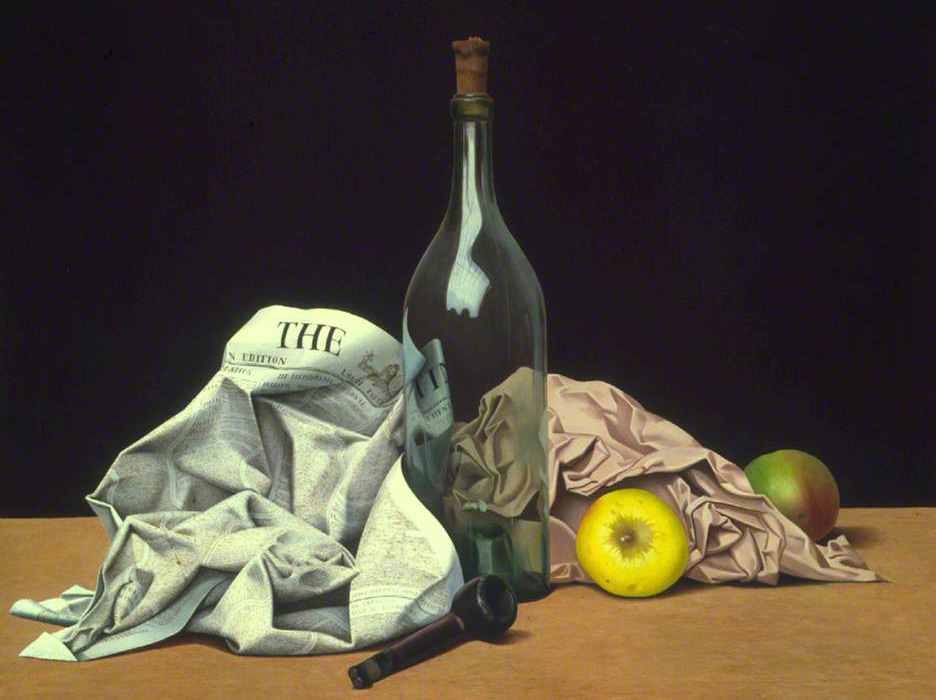

Discoveries for me included The Green Bottle by Tristram Hillier from 1950. Although considered a surrealist painter, this work in isolation has a super-realist quality. The deformed reflection of the window on the bottle in the centre is an appealing sign of light and art history. The pipe at the front adds a touch of humour. Another artist whose work I have seen here for the first time is Rodrigo Moynihan. Moynihan’s White plastic container behind plywood board from1973 is of great beauty and simplicity. The arrangement of objects seems haphazard and yet it draws you in and you forget you are looking at a strangely divided canvas, and instead take in the white plastic container’s luminosity as a peasant from the Middle Ages would have looked at mysterious religious images. I’m hankering after seeing some more of Moynihan’s work. As he was a Royal Academician, perhaps the Royal Academy can put on a retrospective? (Just saying.)

In London galleries visitors are too often left at the mercy of unsupervised screaming toddlers whose parents have abdicated all responsibility, but in Chichester it tends to be pompous men and loud women. I love the Pallant House Gallery, it has an amazing permanent collection, well curated and interesting temporary exhibitions and it is in a beautiful building, but often I encounter here pompous men and loud women who broadcast their opinions to everyone, forgetting that others have come for a personal encounter with painting and have an equal right to enjoy themselves. There is no solution to this problem, alas, and one has to be grateful people are visiting galleries at all.

In the 21st century works featured were largely less significant. I guess time will weed out what is of value. For me it is the quiet works which worked best, and they also happened to be the ones fulfilling more naturally the purpose of a traditional still life. I particularly appreciated Edmund de Waal’s ceramic group September Song II (2020) contrasting different textures, Wolfgang Tillman’s photograph Hampstead Still Life (2020) evoking the quiet but slightly fraught passing of time, and Mohamed Sami’s painting Sunday (2019), a simple interior of light and shadows. Where de Waal shows what will remain in all its beauty and challenges us to see the complexity in what at first appears to be a simple peaceful piece, Tillman and Sami suggest a calm unease with the passing of time, which is really what best still lives are all about.