Art

Cezanne au Jas de Bouffan

Musée Granet, Aix-en-Provence

4/5

Becoming Cezanne

Aix celebrates its master painter with a well-curated exhibition of his beginnings and development at Jas de Bouffan, family mansion with extensive grounds on the outskirts of town. Concentrating on the works created at or associated with Jas, mainly from his earlier output, this overview displays some rarely seen paintings, watercolours and drawings, sourced from many international collections, which provide a different perspective on the importance of Cezanne’s early surroundings. It has to be said that the town of Aix has made an impressive effort to welcome a large number of visitors to this special exhibition, providing well-organised access and adequately restricting the numbers per session, so that there can be enjoyment not only queueing.

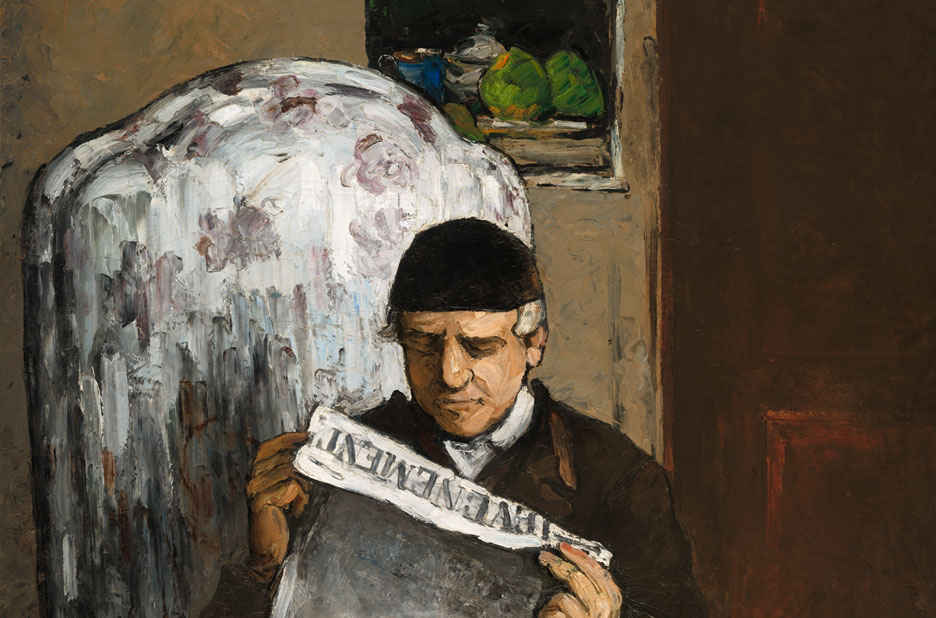

One of the early discoveries are Cezanne’s paintings on the salon walls painted directly on the plaster whose layout has been recreated for the exhibition. It is exciting to see these obviously derivative and stylistically unremarkable early monumental works as they chart the provenance of Cezannian landscape motifs and the seeds of his development. The occasional prominence given to the sky and the trees is particularly endearing and playful. The human figure is malformed and rustic and it would take several years before it becomes compelling and interesting, although the early portrait of the father stands out with its powerful presence, composition and evocation of character in between the bucolic four seasons. Interesting to think that this traditional father allowed his son to decorate the salon in this manner and to use it as his artistic playground. However strict and unsympathetic he may have been to his son’s artistic vocation – we know that he would have much preferred him to have become a lawyer, and also that Cezanne had to tiptoe around him in order to keep his allowance – Louis-Auguste obviously did give him considerable leeway to do as he pleased. He even built him a studio inside the house once it was clear that Cezanne will not follow his designated career path. Nevertheless, although a sanctuary, for Cezanne Jas de Bouffan was always “my father’s house”.

Cezanne painted his father as if attempting to understand him and the depictions are often intriguing, showing a man who never looks at the painter, focusing on his newspaper or something outside of the painting’s reach. In the well-known Portrait of the artist’s father one of Cezanne’s early still lives can be seen hanging on the wall behind Louis-Auguste denying him complete control. The dynamic between the father and son we glean from the paintings is fascinating, exposing fearful but reluctant respect as well as gentle analysis and mockery. The fact that Louis-Auguste is painted reading the newspaper even on the walls of the salon, suggests that appearing busy was a frequent activity creating a deliberate barrier to communication.

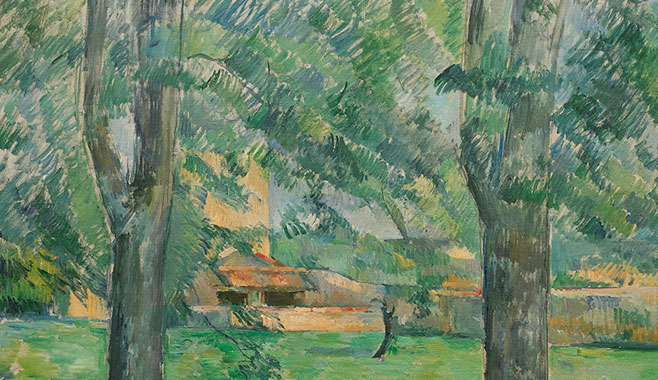

Cezanne’s palette visibly lightens and warms up as we move through the rooms and his stroke shows increasing lightness and sophistication. Jas de Bouffan functioned as a sheltered nursery and outdoor playground for Cezannian landscapes. At first Romantic and ordinary, they become increasingly stylised and enchanted. This 20th century artist and 19th century man never crosses the line into sentimentality and remains firmly rooted in the materiality of the landscape even when he allows himself a certain stylistic distance. It is this discipline, learnt and part of his temperament, and which is absent in his early playful wall paintings, that makes him stand out against his contemporaries.

One room is dedicated to depictions of bathers refined across several canvases. It is not a subject I find particularly appealing because it comes with expectations that the male gaze needs to be satisfied without fuss or objection. Nevertheless there is a beautiful almost classical drawing of a male bather owned by the estate of Jasper Johns, whose eye flashes blue. In the most stylised group of bathers from the Art Institute of Chicago, the bathers have impressively become a mass unified by its colour and texture, geometric and organic at the same time. Precursor to the cubists, some would say, but to me they seem an end in themselves, the outcome of Cezanne’s consistent approach to bodies as painterly matter.

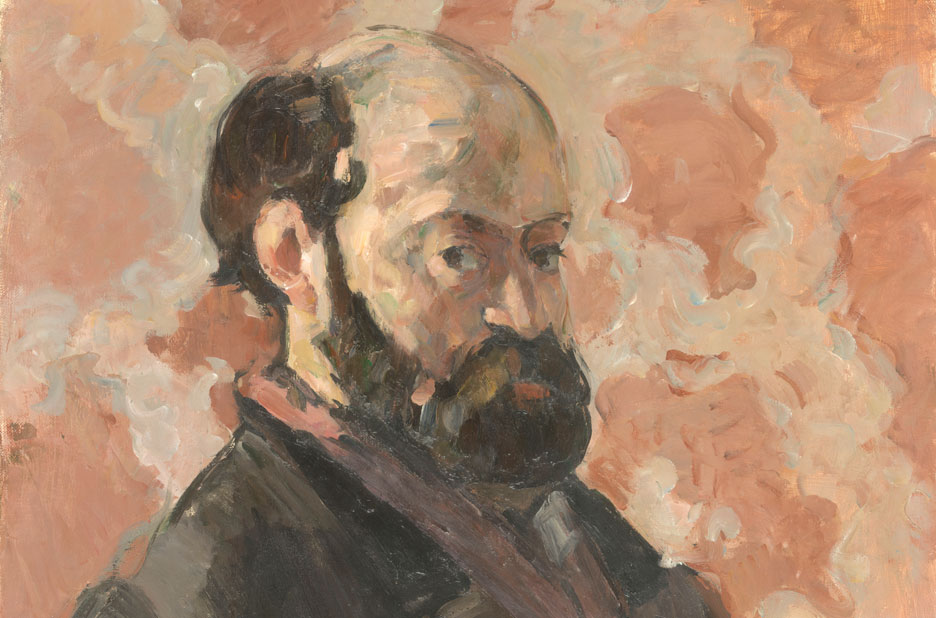

Several self-portraits are included, all ego-less and unshowy, frequently in three-quarter view, exercises in composition and trying to see himself sideways more than portraits of self. In the small self-portrait from the Goulandris foundation, perhaps the most self-confident of all, the subject looks at himself openly and decisively. My favourite is still Portrait of the artist with pink background from the Musée d’Orsay, the coy expression on the painter’s face contrasting pleasantly and somewhat humorously with pink blotches of the wallpaper. There is something ingenuously humble and captivating about this shy man trying to paint himself as he finds himself.

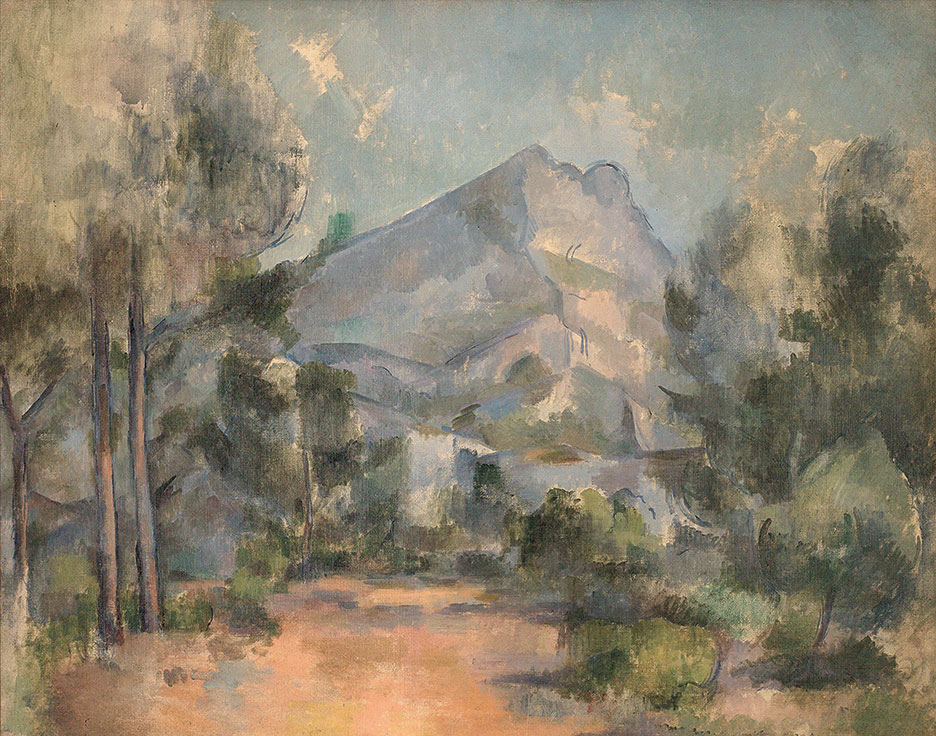

There aren’t many paintings of the Montagne Sainte Victoire, I guess they would have needed an exhibition all to themselves, but we get to appreciate a more unusual version from 1897 that was for a long time considered lost and was rediscovered in 2014, now displayed in turn at the museums in Bern and Aix. The mountain, which in Cezanne’s time could be glimpsed from the grounds of Jas de Bouffan, looms large and monumental, the granite blue, the earth of the path russet and the view framed by trees.

In the end it is the paintings of the mansion grounds that entice the most, showing the maturing hand and mind of the painter and again pointing out the kind of landscapes he was most drawn to and which over time coalesced into recognisable motifs. Clumps of established trees with crossing branches, the soft and complementary hues of reddish-brown earth and the southern light filtering through trees, to name but a few. The painting that closes the exhibition, The gardener Vallier from the Tate, painted at the end of Cezanne’s life is the one I never tire of seeing. Painted at the Lauves studio in Aix, this last portrait is a fitting summary of a life’s work, the face deliberately shielded and undefined, and the light tamed as if observed underneath the rim of a hat.