Art

Seeing Each Other: Portraits of Artists

Pallant House Gallery, Chichester

4/5

Creative intimacies

How do artists portray each other? I’m not surprised Pallant has taken on such an interesting and ambitious exhibition topic. Although the quality is somewhat uneven and some of the more recent works in particular don’t feel like they deserve a place, among the medley little gems can be discovered and admired and lead you to explore unknown connections and histories further. The works are all by British artists and are mainly ordered by period, from older to newer, which was probably the only way they could have been organised considering the immense variety of output. Ordered thus it was easier to spot connections between groups of artists and discover relationships that were never apparent from these artists’ other works. However, having said that, I felt the light-touch curation could have been more substantial and tackled some of the obvious themes in more serious detail.

The work can be categorised into three distinct groups. First, portraits where artists are treated just like any other model, such as the wonderful Dod Proctor’s Eileen Mayo, n.d. It’s always exciting when a Proctor painting pops up at an exhibition, and this one did not disappoint. It is so similar to Morning, Proctor’s most famous canvas, in its colour, style, texture and mood that I initially mistakenly thought it features the same sitter.

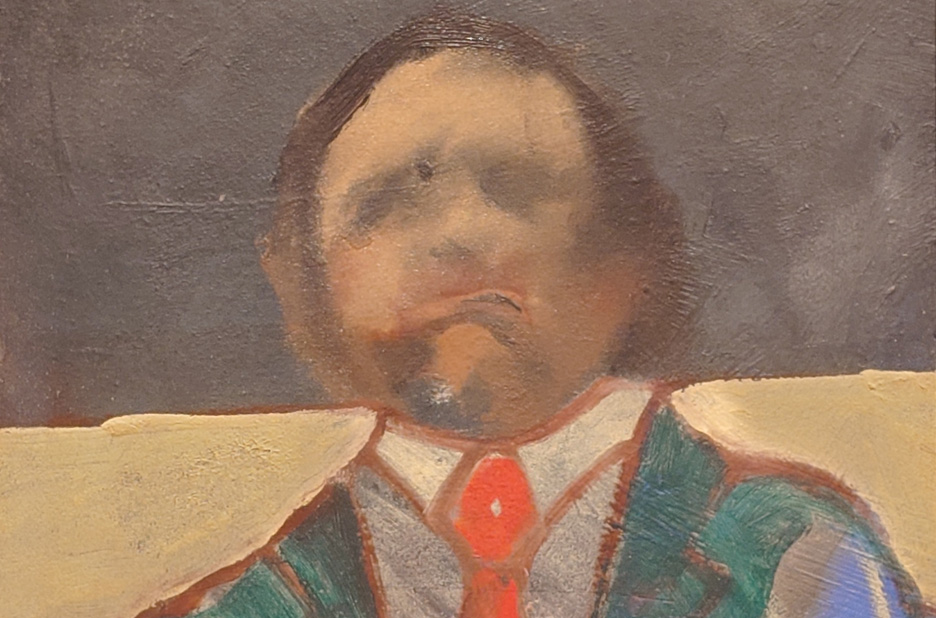

In the second group are portraits of revered teachers and predecessors. The exhibition starts with a painting of Augustus John which belongs to this category and so do several excellent but perhaps too respectable portraits of Walter Sickert. Habib Hajallie’s black and white ballpoint pen portrait of the otherwise colourful Sir Frank Bowling from 2023 conflates Hajallie’s admiration with the sitter’s pensive melancholy.

Finally we get to the third and most thought-provoking group of works and those are ones of friends and lovers. I regret that Roger Fry’s portrait of Nina Hamnett looks too tame to contemporary eyes. But there are many other more noteworthy works on display.

Female friendship is captured in exchanges between Chantal Joffe and Ishbel Myerscough. We can examine some of their humorous and convivial painted correspondence created over the years, but the highlight is a painting by Joffe entitled Studio from 2025 showing her and her friend as two middle aged women in bras and unflattering tights pulled up high, facing the viewer and laughing at themselves. Hilarious self-mockery is a rare gift in art. Perhaps an unflinching borderline-cruel representation of yourself is more easily achieved when accompanied by a friend. I was also captivated by the contrast between Proctor and Joffe’s paintings: Proctor’s gentle sensual and texture-rich portrait versus Joffe’s rough canvas subverting the traditional female depiction and refusing to please.

This will not come as a surprise, but generally speaking there is a scarcity of portraits of women artists showing them at work. Also the female body is still more often the focus than it should be. Comparing the portraits featuring women and men, the inequality which favours men is still very apparent. It is unfortunately something we have grown used to. Even though they challenge it to an extent, Joffe and Myerscough have also absorbed this social expectation.

The story of Paula Rego and Victor Willing’s relationship is fascinating and seemingly rich in painterly exchanges. There are several humble drawings on view and the one that sticks in my memory is a potent little one by Rego of Willing sleeping. It exposes the vulnerability and dreams with subtle and minimal means from a slightly unnerving and unappealing claustrophobic viewpoint of closeness. I see right into you, the drawing seems to suggest, and yet, does it really? Can we ever really know someone? This drawing is a perfect representation of this timeless conundrum.

In response, there in a pastel drawing of Rego by Willing, soft and yet one eye is shadowed by the arch of the eye socket, pointing out this anatomical feature of Rego’s face, but also hinting at something darker and more troubled.

Portrait of Victor Willing by the seaside, 1967, by his friend Michael Andrews is both quirky and endearing like a private message between the two friends. At first it looks like an unflattering fuzzy picture of a mad scientist until you read the caption that the subject has popped his head into a face-in-hole board. What makes this funny and moving is that the incongruousness of the head inside its adopted cardboard disguise suggests the perception of the general incongruousness of a body in the world. It is as if Andrews perceived the contrast between his friend and the world around him and when Willing stood behind the cardboard model, this contrast was magnified creating a hilarious moment. The painting contrasts and resonates with the startling and moving Willing’s self-portrait in Pallant’s permanent collection.

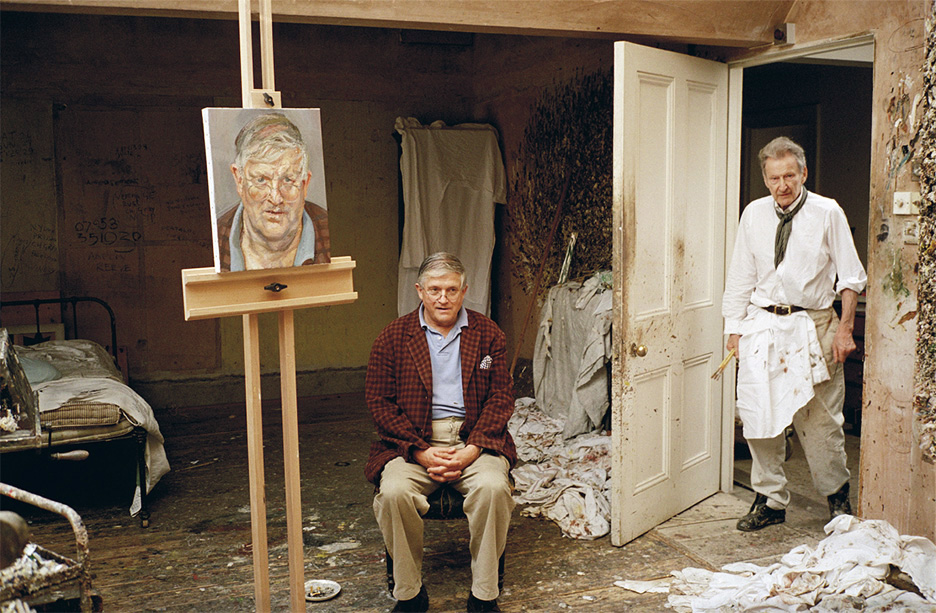

The photo portrait section is surprisingly interesting except for a large display of annoying and frankly awful holiday snaps featuring an assortment of people some of whom may perhaps be called artists. The most accomplished is a black and white photo by Bill Brandt from 1956 of Ben Nicholson drawing. The composition is superb, alternating contrasting black and white areas with Nicholson shown at an angle from behind, his upper arm with a rolled-up sleeve in the centre. You feel the intensity of Nicholson working as if you were in the room. Another excellent one is of Auerbach’s hands by Nicola Bentley from 2015. And in another room there is the extraordinary photo by David Dawson from 2002 of Freud painting a portrait of Hockney, the model obediently sitting while Freud is gripping a brush in his fist and facing the photographer like a wild animal.