Art

Hiroshige: artist of the open road

The British Museum, London

4/5

Enduring fascination with Japan

Japanese prints produced during the Edo period, just before Japan opened to the West, symbolise for the European and Western mind a visual synthesis of Japan’s uniqueness, which is why we are still fascinated by them even though they are today easily accessible and available and have become a basis for pictorial shorthand which we all recognise. Utagawa Hiroshige is one of the greats of the genre and the newly available examples from the Alan Medaugh collection gifted or loaned to the British Museum form the essence of this new exhibition which is well worth braving the queues to enjoy.

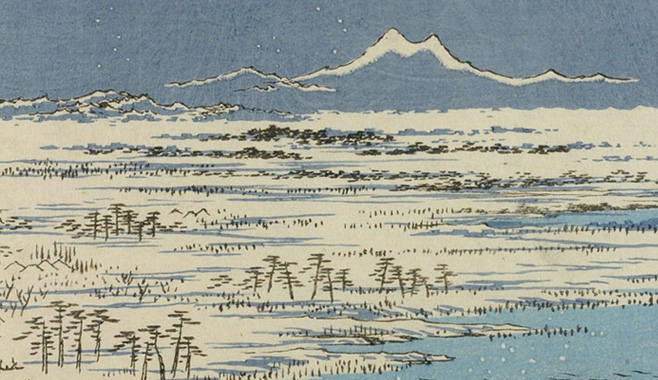

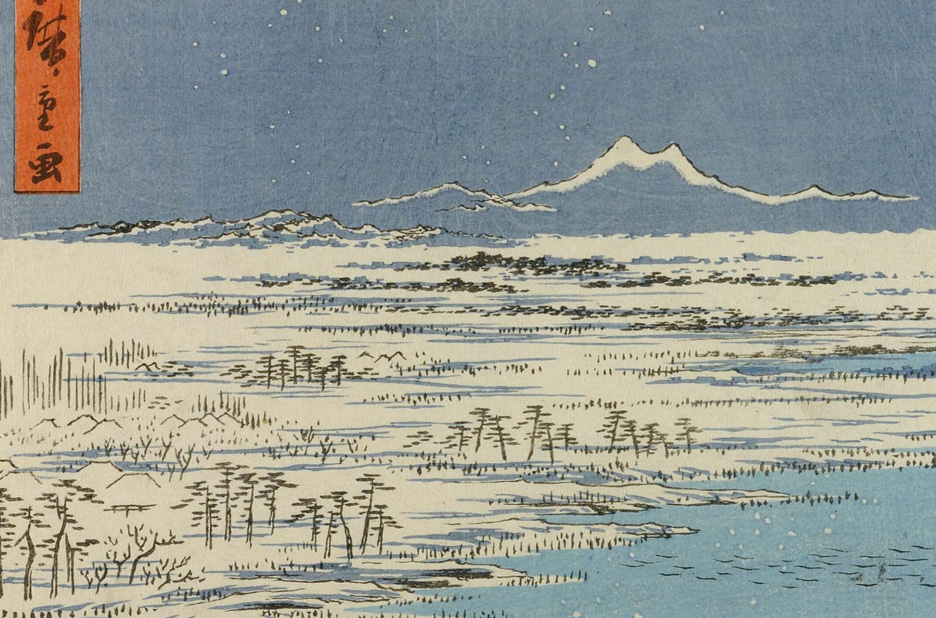

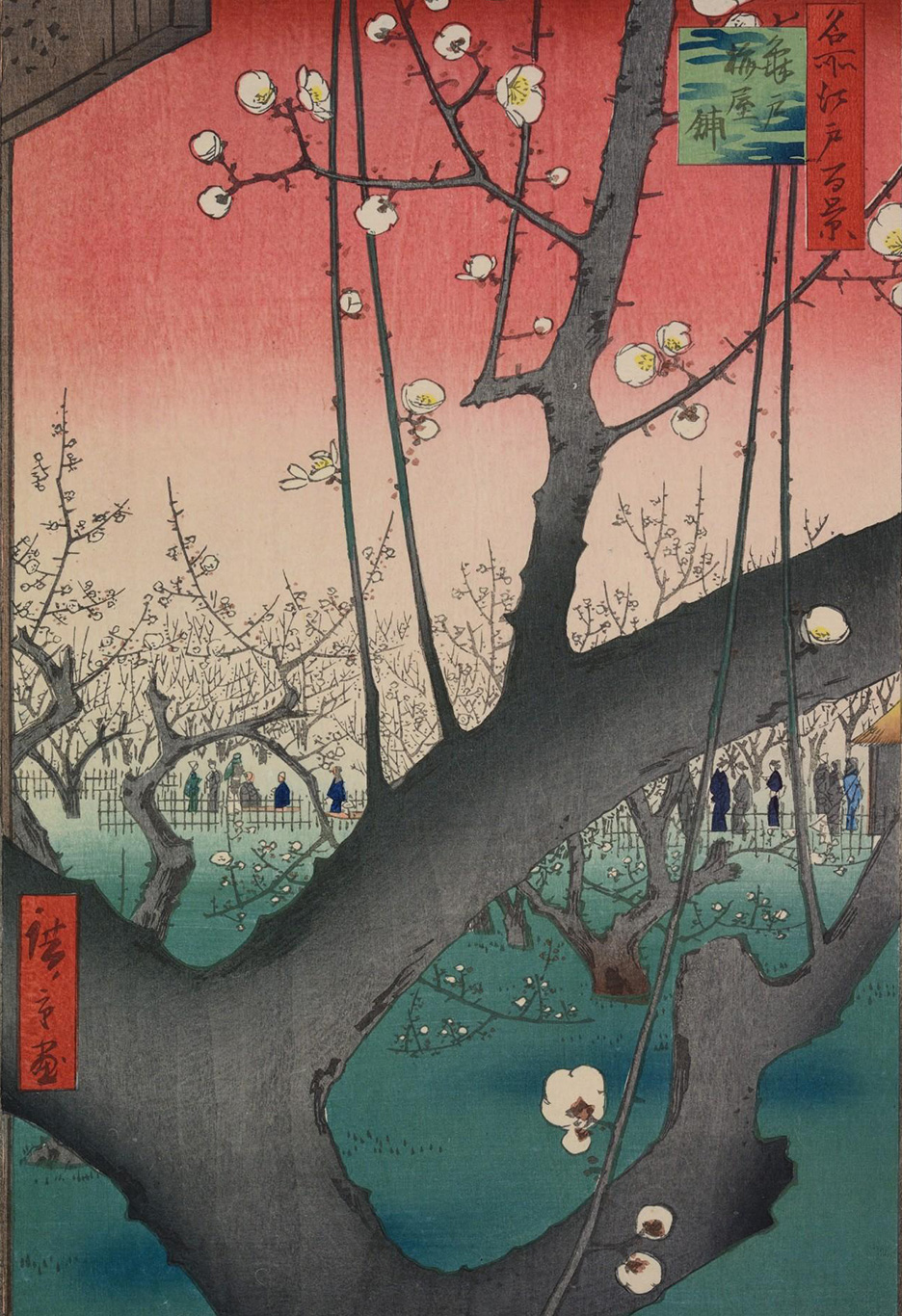

Hiroshige’s most famous prints are the ones in the collection One Hundred Famous Views of Edo published in 1867 which are always interesting to revisit. The most famous of all, Sudden shower over Shin-Ōhashi Bridge and Atake, gives us an engrossing depiction of a sudden downpour with diagonal lines representing rain. Many of the striking dynamic compositions in this collection combine extreme close-ups with wide open long-distance landscapes and beautiful atmospheric bokashi gradations. 10,000 league plain of Susaki at Fukagawa is one of my all-time favourites with the eagle-eye view of the endless plain in winter beautifully annotated with simple short lines representing groups of trees and crowned with the snowy outline of Mount Tsukuba. But the undoubted highlight is seeing the first edition of The Plum Garden at Kameido with its glorious red and green morning colours and gradations. The plum tree in the foreground reveals between its branches a blossom party in the background.

Perhaps the most illuminating group in this exhibition are the fan prints, made for the oval hand-held uchiwa fans. Hiroshige produced more than 500, which is more than any other artist. The shape of the fan gives an opportunity for interesting compositions where the narrowing in the middle is used to its advantage, hinting to what is hidden or ignoring this blank area altogether the better to balance the design. There are three examples that catch my eye from Famous Places in Edo (1849-51), all with beautifully preserved colours. On ‘Snow’ the red highlights on kimono underlayers, labels and boxes hold the balance. And the narrowing happens to be exactly where we could have a mound of fresh snow. The example below is unfortunately an inferior copy and the colours are not as rich as what we saw at the exhibition.

Evening Cool at Ryōgoku (1847-8), a triptych showing three women on the Sumida embankment at night, enticingly brings to life the contrast between blue darkness of the warm night at a water’s edge and the bright portraits of women in their beautiful attire. The most colourful is the lady in the middle holding her uchiwa fan in her teeth while adjusting her obi. The full moon shines on her behind the tree and meets her gaze. It’s only in Japanese prints that I have seen this ability to show off the night as dark but vibrant while presenting the figures in full flat light as if on stage.

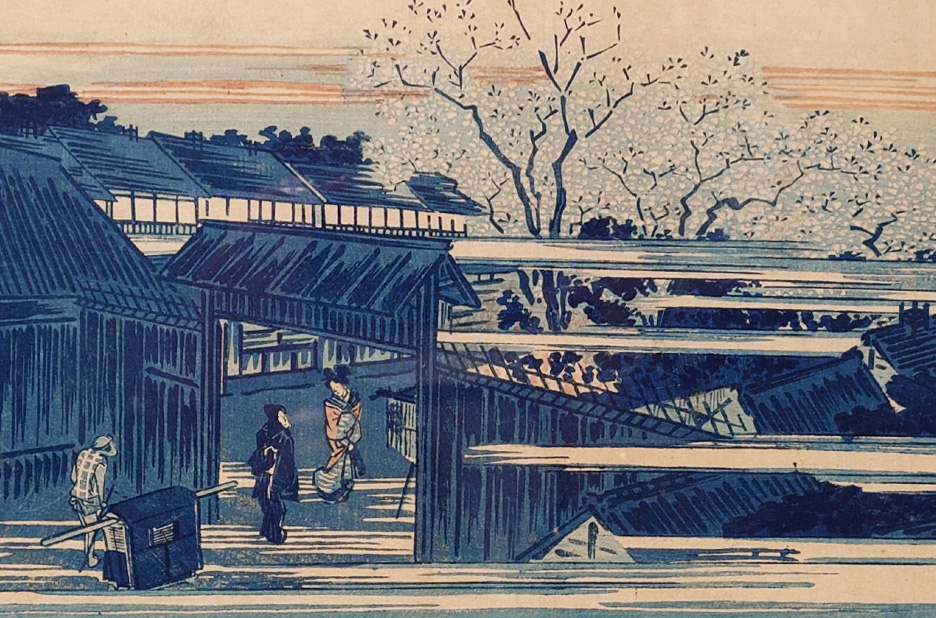

Some designs were reprinted with different colour variations, and an early blue aizuri-e version of Morning Cherry Blossoms in the New Yoshiwara (c. 1831) enchants with it vivid representation of the cool hours of dawn with horizontal mists. The variations that are the result of random factors can make the seemingly anomalous prints all the more interesting and unique. Another aizuri-e fan print, the minimal Raftsman poling logs on the Sumida River near Mimeguri (mid-1840s), captures the simple fluidity of the artist’s brushstrokes. With Japanese prints in general, there is such richness in the detail and it’s always beneficial to be able to get close enough to see it.

In the birds and flowers section the British Museum uses the opportunity to showcase part of its holdings, such as the lyrical Owl and maple tree (c. 1830). Overall I wish there were better prints from the excellent museum collection on show, although I appreciate that the purpose of the exhibition was primarily to highlight the new acquisitions and show the development of the artist.

The last section concentrating on Hiroshige’s legacy is disappointing in its weak choices. Utagawa Hiroshige II and III are not a patch on number one. It does seem that with Western influence, the Japanese art of printmaking is irremediably altered. In the West however, the influence of Japanese prints was productive. A lone postcard of Whistler’s Nocturne cannot make up for the lack of the painting itself. And it would have been a perfect example of Hiroshige’s legacy. It’s that rich night again, but in a completely different climate, together with a portrait format, vague distant figures and a dynamic cut-out composition. The most successful example shown is Van Gogh’s ink drawing La Crau from Montmajour (1888) which was recently shown at the Van Gogh exhibition at the National Gallery. Here is an artist who fully absorbed the Japanese lessons and made them part of his unique vision. In Van Gogh’s own words:

“… an immense flat expanse of country – seen in bird’s eye view from the top of a hill … streaming away like the surface of a sea towards the horizon … It does not appear Japanese, and yet it is the most Japanese thing I’ve ever made.”

And we have to agree. It is difficult to fully pinpoint what makes this drawing seem an obvious continuation of the exhibition. The perspective, the brush strokes, and the awe of looking at a dynamic landscape created with apparently simple means.