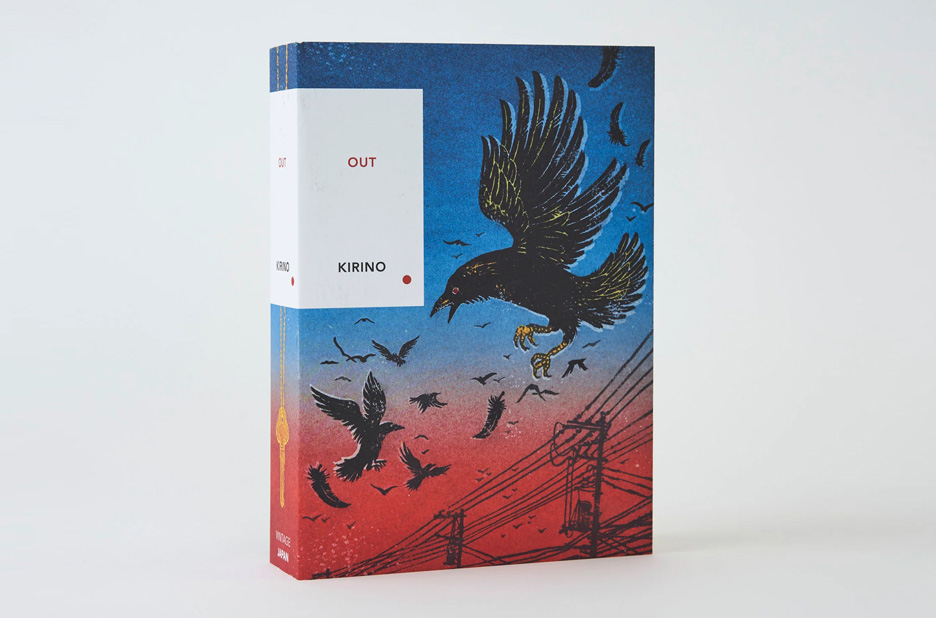

Book

Out

Natsuo Kirino

5/5

Irresistible feminist noir

Having recently visited Japan, I have been looking for some contemporary Japanese fiction in English (other than Murakami) that I would like. Most of the novels I picked up were at best flat and somewhat tentative and at worst banal and sentimental, leading me think that this may be how the Japanese tend to write. There were even a few I started and couldn’t finish. You could say someone’s ‘wishy-washy sentimentality’ is another person’s ‘sophisticated understatement’, but I do very much appreciate the sophisticated understatement in Japanese cinema. Then I decided to try Natsuo Kirino’s Out. And what a fine and amazing novel it is. I almost never read crime fiction, but something about the description of this novel made me want to give it a go. And I’m really glad I did.

Some reviewers have called it an example of ‘feminist noir’ and I think this is a good way to describe it. Although the novel is nearly 500 pages long, it draws you in and is a fast read. The writing is lean, direct and to the point, probably the complete opposite of other Japanese fiction I have tried. The dialogues are masterful, and the descriptions of the ambiance very vivid, which is why I am not surprised to see that it was adapted into a film (one more thing on my list to locate). Towards the end it gets gory, but it is all consistent with the characters as they have been developed.

Four women work the night shift in a Tokyo bento factory. They have different difficult circumstances and different characters but have formed a loose alliance in part bound by survival and friendship. Masako, the main character, could be said to be the leader of the group. She has a cool head and everyone trusts her to know how best to proceed. She lives with her husband and teenage son with whom she barely communicates. Yoshie, aka ‘Skipper’, is the eldest member of the group. She is also very organised and competent at work, but at home she has her hands full with her teenage daughter and spiteful paralysed mother-in-law, not to mention her older estranged daughter who dumps her young son with her and steals her money. Pretty and conforming Yayoi has a husband and two pre-school sons. The youngest, Kuniko, is superficial, greedy and treacherous. The plot starts unfolding when Yayoi strangles her abusive husband who has spent all their savings on gambling and prostitutes. The delicate Yayoi kills him the way a man would kill, using his belt. The three friends then gradually get involved to dispose of the body.

It struck me that the four women also represent four stages of women’s lives: careless self-centred youth, hopeful efforts to fit into patriarchal expectations, disillusionment with life which often strikes in middle age, overwhelming caring duties.

Much more than a crime novel Out is a fascinating and bleak critique of Japanese society and its patriarchal and misogynous structures which give women no way out. In an oblique way it reminded me of Stieg Larsson’s The girl with a dragon tattoo, another novel which uses the crime genre to really talk about how deeply misogyny is embedded in society and what it takes to be a survivor while female. Interestingly Out was written in 1997, but to a non-Japanese it reads as contemporary.

Kirino states that what she doesn’t like about detective stories is looking for criminals, and indeed in Out we are shown who committed the crime straight away, the interest lies in the fallout from this situation particularly within a group of marginalised women.

Kirino’s belief that there is no such thing as society and that we are essentially solitary creatures permeates this novel. Everyone is isolated and alienated without any recourse. This resonates with me profoundly and is a fertile condition for an unflinching analysis of what isolation can lead us to. In this sense and also in terms of her simple direct style of writing you can understand Kirino’s affinity with Agota Kristof’s underrated masterpiece The Notebook.

Having had a quick check of online reviews, I note that some male reviewers seem to not really get this book. I guess it is not surprising, it’s not about them.

Out is translated by Stephen Snyder