Art

Kiefer/Van Gogh

The Royal Academy of Arts, London

5/5

Kiefer has eaten Van Gogh!

I was concerned that this exhibition may not be very good. Juxtaposing two artists, one immensely famous, revered, unique and dead, the other a contemporary star, sounded like a recipe for disaster and disappointment. However, despite being a much reduced version of the exhibition originally shown at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, this overview really pulls it off, a testament to Kiefer’s excellence as well as exemplary curation.

I don’t know how much input Kiefer had in terms of curation, but he strikes me as a control freak and I wouldn’t bet against him having engineered the selection and the grouping of the works. Having seen Wim Wender’s excellent film about him called Anselm (2023), it is clear to me that this man is completely absorbed in the act of creation, which for him is intensely physical. In his huge warehouse, Kiefer wizzes around on his machinery, and blowtorches canvases to stunning effect. This is not a man who would let some curator make decisions about his work, certainly not in his lifetime.

As I entered the exhibition with trepidation, I saw the blackened vertical sunflowers with the painter lying horizontally underneath them in the first painting Hortus conclusus 2007-2014 and I heaved a sigh of relief. All will be good after all. Bar his predilection for Latin names which I feel is unnecessarily stuffy and doesn’t suit his work, Kiefer is able to measure himself against Van Gogh as his idol. The blurb next to the painting talks about savasana or corpse pose, but this is so much simpler: the painter expresses his endless reverence for the sunflowers, symbolising Van Gogh’s work, that he is admiring lying on the ground below them. The huge height of the canvas and the distance between the tallest sunflower and the horizontal body could be thought to signify the distance Kiefer perceives between him and Van Gogh. He equally expresses his physical fear that the excellence of his predecessor will bury him underneath his mastery. It is a strong and very well constructed painting which is impossible to really appreciate in reproduction. The title means ‘enclosed garden’ suggesting a private conversation between the two painters. Was Kiefer any weaker in his art, I would have called him a fraud, but his attempt to have an exchange with his hero equal to equal, bears fruit in this stunning woodcut collage. The biggest and tallest sunflower in the middle shines on Kiefer’s figure at the bottom and us, like a black sun, symbol of depression, but also of the distilled essence it is reduced to by the power of the sun.

To accompany the exhibition we are issued with a small booklet with translated entries from Kiefer’s diary when as a young painter he went on a Van Gogh pilgrimage around Europe. This is an interesting testimony of how he thinks about and connects with Van Gogh’s work. This sentence from the diary would be a good subtitle to Hortus conclusus. “The heat covers it all, as if everything’s been petrified for a hundred years.”

Follow a couple of large canvases engaging with Van Gogh’s theme of wheatfields and their visiting birds, crows and ravens. Nevermore from 2014 and Crows from 2019. In Nevermore with rugged impasto or more accurately an agglutination of matter on top of the canvas, which is characteristic of most Kiefer’s works, the golden wheat stalks crisscross mirroring the shapes of raven’s wings in low flight. Unlike Nevermore where a bit of turquoise blue sky and greenery shows through, the Crows are more earthy, the stalks scorched and blackened by the sun whose heat and light in gold leaf take up the entire sky. Even if at first these paintings seem rough, rustic, crude, the longer you look at them, the clearer the composition becomes. Kiefer’s style is almost a deterrent, a defensive move to turn away those who don’t put in a little bit of effort to understand his canvases. After a while, you get used to the monumental roughness and are able to glimpse the world beyond.

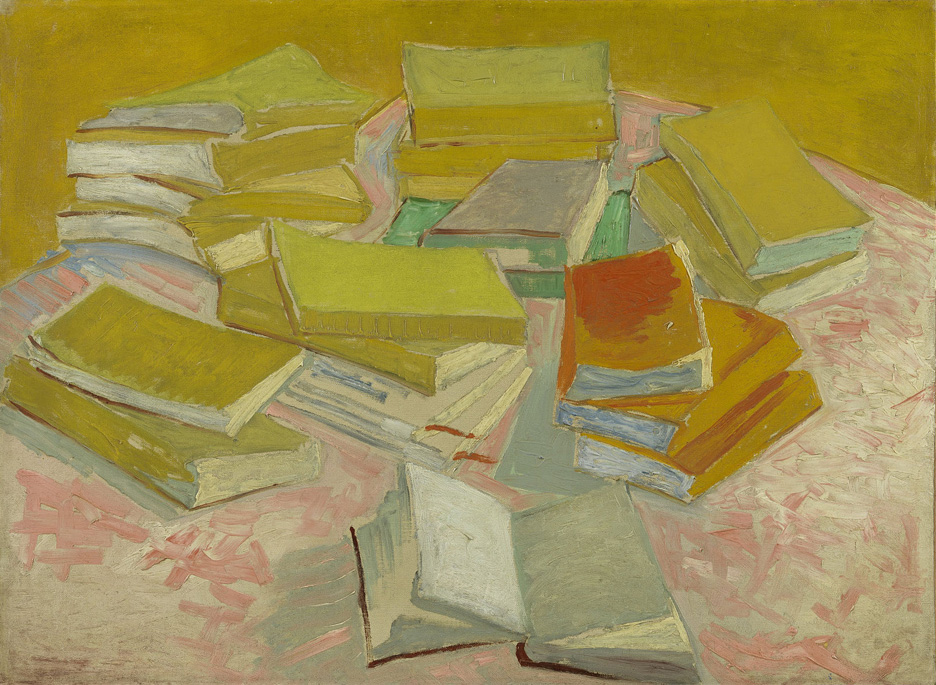

In this first room we also see Van Gogh’s Piles of French novels from 1887, the prettiest painting in the exhibition with its harmonious yellows, pinks, oranges and greens, displaying several French paperbacks on a table. There is no obvious parallel with Kiefer’s canvases in the exhibition, although the theme of a stack of books appears frequently in his work. Both painters have a predilection for yellow and golden yellow, both are great readers. The books are the chosen visual objects, for their shape, texture and colour (cheap French novels were yellow in those days). The curator Julien Domercq apparently deliberately chose Van Gogh’s works that have less of a direct connection with Kiefer. That way Van Gog’s presence was not completely obliterated by Kiefer’s much more aggressive and bigger canvases.

The strongest Van Gogh here is Poppy field from 1890. It shows the landscape textures which fascinated Van Gogh and which Kiefer also absorbed through his influence. And there is yet another variation of the view of La Crau from Monmajour, the third one I have seen in the last year as part of different exhibitions. It is a stunning drawing like the rest of the series and I’m glad it is of interest to Kiefer. It is a humble work in appearance showing horizontal textures of great variety which hang together delicately to present a sweeping view.

In the last room there are two stunning monumental canvases by Kiefer. The last load from 2019 shows a wheatfield which has been cut and burnt, with one last stack left to be picked up. The ominous implications of the last healthy bunch of wheat on blackened earth can be read as a warning about the last vestiges of democracy, or of the planet ecosystem, but could equally represent a stage in the repeating agricultural cycle.

Kiefer’s canvases are so large that you get completely different readings and perspectives depending on whether you are looking at the whole or at the detail. He has developed a stunning and rich way of representing vegetation in different stages of disintegration which is fascinating to look at up close. This obsession with wheat and stalks in general speaks to the environmental anxiety as well as the various modes of expiation for the destruction of the Second World War. The good Germans are simply not allowed to get past the horrors of war. And when you thought they just might perhaps in twenty years’ time be able to call it the past, the political landscape changes in such a way to make it all painfully relevant again.

The last painting of the exhibition, The starry night from 2019, answers Van Gogh’s impossible painterly challenge. What is swirling in the sky are not stars and their trails, but golden locks of straw. Kiefer here transcends his natural bleakness. Using plentiful messy piles of straw, he disarms viewers with his technical and compositional mastery of recreating the awe and joy of Van Gogh’s starry sky. But this is not a simple recreation, Keifer evolves the concept effortlessly while still referencing the original. With the background of same lovely light turquoise previously seen in Nevermore the painting celebrates the enduring cycle of life.

The question is, is this an exhibition of equals, and if not, which painter dominates? Does it demonstrate Van Gogh’s influence or Kiefer’s appropriation? Is the exhibition about Kiefer and how he integrated Van Gogh’s influence or about Van Gogh and how he influenced Kiefer? I would have to say the former. Of course we don’t see the strongest of Van Gogh’s canvases here which may have put Kiefer to shame. We also don’t see many Van Gogh canvases in comparison to a larger selection of Kiefer’s work. The exhibition title is misleading, perhaps it was more accurate for the original larger exhibition in Amsterdam. We have a display of Kiefer’s work showing how he has digested the lessons of Van Gogh over time and incorporated them into his equally unique universe. A revelatory and rewarding experience.