Art

Edvard Munch Portraits

National Portrait Gallery, London

4/5

Late relaxed vibrancy

In this compact overview of Munch’s portraits, it’s the late works which impress the most with their emotional astuteness enhanced by vibrant colour treatment.

Munch’s portraits provide a healthy contrast and perspective to his better-known works depicting anxiety, sickness, bereavement, religious guilt and a tortured understanding of women. They offer a different calmer sensibility, an appreciation of others instead of introspection and demonstrate the development of the artist’s style over the years. If you love Munch’s disturbed symbolic works and cannot imagine the painter could be truly authentic painting in any other way, then this exhibition is not for you.

I will never forget when years ago in an American museum shop I saw my first ‘it’s a scream’ mug, a shocking example I thought at the time of the shallow commercialisation of art. What was even more inappropriate in my eyes was that a work describing genuine angst was transformed into a mug mocking that angst which someone who loves art would be expected to find attractive or humorous enough to buy. Now I find it amusing that we have a scream emoji, although I still feel a pang of the old discomfort at this further commodification. Understanding of Munch the artist has suffered from the overwhelming fame of The Scream which happens to be also one of his early works, and so it is a welcome move by the National Portrait Gallery to throw a light on other aspects of his art.

Initially and inevitably the subjects of Munch’s portraits were his family. The execution of these early portraits is fairly traditional and from this period I lingered the longest in front of a radiant canvas of his sister Inger in the sun I remember from the Bergen Art Museum. Then Munch started portraying friends, benefactors and models. Initially these were also more traditional, then symbolic and finally partly post-impressionistic and fauvist. The majority of the most interesting works have been lent by Munchmuseet in Oslo, with a few contributions from Bergen.

I was hoping that the exhibition would be more substantial and feature a stronger selection of works, but overall it gave a decent overview of Munch’s output in this genre. Nevertheless, I do wish that instead of the indifferent portrait of Nietzsche’s sister, no doubt matching her personality, probably only included to bolster the ratio of women portrayed, we got to see the excellent portrait of Nietzsche against a blistering sunset from Munchmuseet. But fortunately there was better stuff to follow.

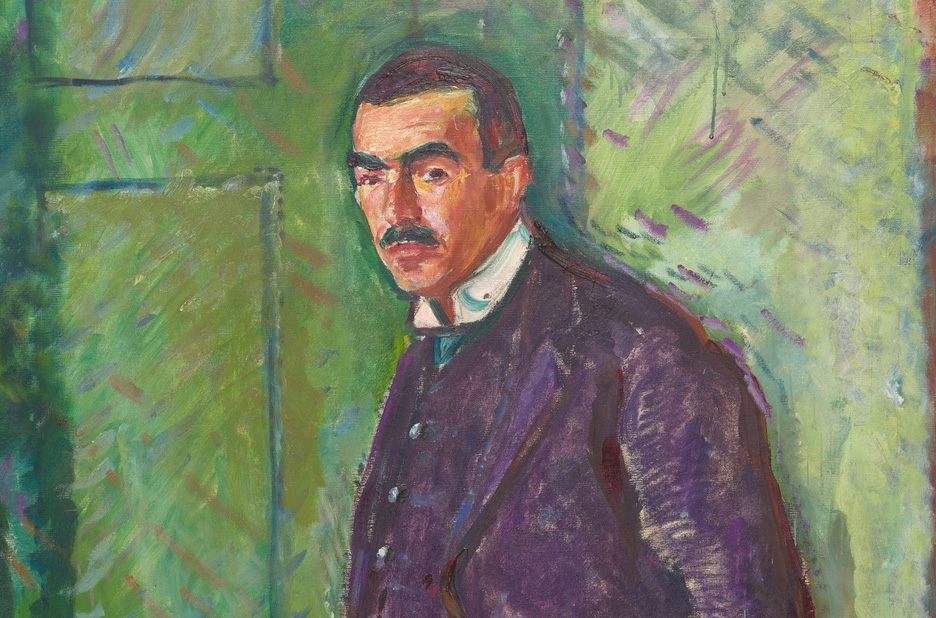

Out of several full-length portraits the most interesting were the ones of the powerful German industrialist Walter Rathenau from 1907 and of Munch’s friend, writer and art critic Jappe Nilseen from 1909. Nilseen is depicted in a vibrant dark purple suit in three quarter view on a background of bright green and red. His posture is relaxed with his hands in his pockets and he looks us in the eye, calmly and intelligently sizing us up. Nilseen didn’t think he was portrayed very kindly, but to contemporary eyes this canvas seems flattering. Diagonal brushstrokes in the background and the white shimmering accents on his suit inject dynamism to Nilseen’s static posture and serious demeanour. You get the impression of a man reluctantly portrayed, but the bravado of the colour scheme confidently puts him on a pedestal.

The portrait of Sultan Abdul Karem (1916) was an interesting discovery. This painting of a black man with his eyes closed wearing a vibrant large green and black striped scarf is supported by a complementary colourful background with a large orange-red block on the left. The outlines of the man’s suit and scarf together with his impassive face give an initial suggestion of an African mask and the painting radiates calm and self-containment. Munch seems to have enjoyed this opportunity to build the colour palette around the colour of the sitter’s skin and the result is striking and beautiful. There seems to be a lot of outrage that Munch didn’t name his sitter which is ridiculous in the context of art history where most models are not named. Some critics seem to be neurotically on the lookout for anything that could be construed as racist in his paintings of Sultan Abdul Karem. There is no doubt that Munch was a man of his time in many ways, including his reactionary views on women and race, and his use of what we consider to be racist language today, but in this particular example, if I look at the work itself without immersing myself in biographical information all I see is an excellent and sensitive painting.

Seated model on the couch (1924) shows one of Munch’s frequent models in his later years, Birgit Prestøe, sitting on a sofa in a colourful dress (and note she is not named in the title). It’s one of those paintings where the model is just a pretext, just an inspiration for constructing a composition and colour scheme. It is interesting that Munch often doesn’t focus on the eyes. He doesn’t give them much definition, they are either shut physically or metaphorically, or empty and insignificant. Instead we appraise the sitters’ personality and mood from their posture, from their being in the world. Prestøe’s eyes are very faintly defined, but moreover her proud elegant profile reminiscent of Schjerfbeck’s faces, her long yellow hands and slender neck are just details inside the multicoloured dress whose colours spill out onto the emerald floor and blend into the shadows behind the sofa. The ochre area behind the sitter, a curtain or perhaps part of the view through the window, matches and accentuates the sitter’s hair, and the yellow table with a yellow-blue vase provides alternative focus. It is a visual feast and one of my favourites.

It is a shame the exhibition didn’t include any of the marvellous late Munch’s self-portraits where he completely lost the self-importance of earlier works and gained a self-critical lightness. Perhaps this is for another time. But we got to see one very poignant late self-portrait, Self-portrait by the arbour, painted in 1942, a couple of years before Munch’s death. Coming full circle from The Scream, we see a lonely man surrounded by a vibrant world, this time the man is much calmer and the world no longer bleak and inhospitable. More of a landscape than a portrait, this work is strongly reminiscent of Van Gogh. A faceless figure in a coat and hat, the painter is walking towards us with a depressed gait surrounded by the intense colours of nature that will survive him. A yellow tree behind the man suggests a glorious sunset.