Art

Radical

Lower Belvedere, Vienna

4/5

Multiple modernisms

Ambitious and wide-ranging, this exhibition celebrates the modernism of women artists between 1910 and 1950. It’s relentlessly inclusive, joyfully international, enumerating many different ways in which women made an artistic contribution in this period. As a result we discover many interesting works, but only a few truly stand out as great art. Many different modernisms exist, this exhibition tells us, not all of them radical, but all emancipatory.

We begin with Charley Toorop’s unembellished self-portrait with a frown from 1934, introducing the representation of female gaze and self-reflection. Her modernism is realistic and down to earth and thus of the less sensationalist type, but perhaps more universal and long lasting as a result. Toorop is known for her prolific self-portraits, documenting and probing her own dual identity as subject/object. Later there is another one of her works, Female figures from 1931/32 showing the bodies of three women with unflinching realism.

The exhibition gives priority to many lesser known and neglected artists with occasional works by their more famous counterparts. As far as famous artists included are concerned, adverts for the exhibition misleadingly use images of Lempicka’s paintings, but we only get to see small colour copies of a couple of her works. Germaine Richier is represented with one characteristic sculpture, although not one of her most interesting. Lotte Laserstein’s idealistic nude is included, an excellent work, but again not one of her best.

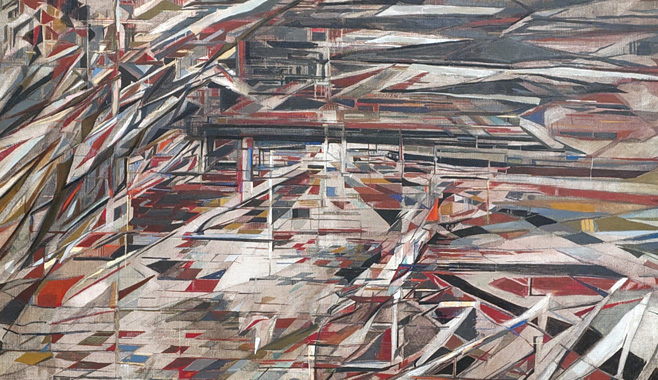

It’s in the field of abstraction that the exhibition more consistently shows artistic excellence. Lyubov Popova with a cubist square landscape, Sophie Taeuber-Arp with a small series of gouaches of subtle curved geometric shapes and most notably Maria Vieira da Silva with her Battle of the knives from 1948. An amazing artist with a very distinct style Vieira da Silva deserves more exposure. Tate Modern in London occasionally trots out one of her paintings it has in its collection and there is an interesting museum devoted to her work in her native Lisbon. The exhibition is right to point out that abstract art helped women artists be appreciated despite their gender by allowing them to avoid revealing their identity. It provided the same type of assistance to international artists.

Just because you are fighting indiscrimination and inequality that doesn’t make you a good artist. A lot of works fall into this category particularly in the protest section regarding fighting the abortion ban of Paragraph 218. Works that are neither particularly good nor have stood the test of time, but were crucial at the time of creation. It is still important to show them and remember that such artistic protests took place, particularly as we are forced to fight for basic rights all over again.

In the protest section, I notice a humble but perfect linocut On Petroleum from 1953 by the black American artist Elizabeth Catlett whose social realist work is reminiscent of Alice Neel. The oil extracting machinery protected on a palm of a hand takes the geographical shape of the USA.

The most impactful discovery of the exhibition for me was that of three very different and unusual works by three artists I have never heard of before and whose field is not painting, but weaving, ceramics and film.

The wool tapestry called Couple in the Garden from 1954 by Ida Kerkovius, a Bauhaus graduate from Latvia, is an anti-painting in many ways. Her rustic and yet abstract representation of a couple in the middle of a colourful garden is simultaneously homely and avant-garde.

The sculpture by the Austrian ceramicist Gudrun Baudisch called Kneeling Girl from 1927 is one of the most accomplished works at the exhibition. The Viennese may be quite familiar with it as it is part of the MAK collection, but for me it was a delightful discovery. This glazed stoneware nude is a confident modern girl with short orange-red hair and equally orange-red scarf wrapped around her porcelain white body streaked with blue dye.

And then there is something completely different: an experimental silent surrealist black and white short film Meshes of the Afternoon by Maya Deren and Alexandr Hackenschmied shot in 1943. Incredibly modern, dream-like, with doubling, repeated actions and patterns. Dream and reality are here impossible to disentangle. The sensitivity of the film is feminist, and if it seems mesmerizingly modern today, it must have been incomprehensibly avant-garde in 1943. Deren was a Ukrainian-born American whose family fled the antisemitic pogroms in 1922. She was a one-off, a true film pioneer whose contribution to early experimental film remains largely unrecognised.

After all it seems that the beginning of 20th century was a good time to be an artist while female. Many personal and political battles aside, the rich variety of work can now never be put back in its box or hidden from view. That is the true radical statement of this exhibition.