Art

Permanent exhibition

Heidi Horten Collection, Vienna

4/5

Newly accessible modern masterpieces

Housed in a beautiful modern space on three floors next to Albertina, this new private modern art collection in Vienna opened its doors to the public in June 2022. The most impressive section is on the ground floor under the title KLIMT ⇄ WARHOL where several exciting masterpieces from its permanent collection rub shoulders. Klimt and Warhol from the exhibition title are there just to provide a time reference and pretty posters. True art is in between.

Jawlensky’s Still Life with Kulich from 1905 is the first to catch my eye. Reminiscent of Chardin’s brioche but thoroughly modern. The Kulich, traditional Russian easter bread, is like a sun the source of yellow and orange light and warmth, accentuated with several oranges dotted around the table. Jawlensky always has something new to say with his striking compositions and intense colouristic solutions.

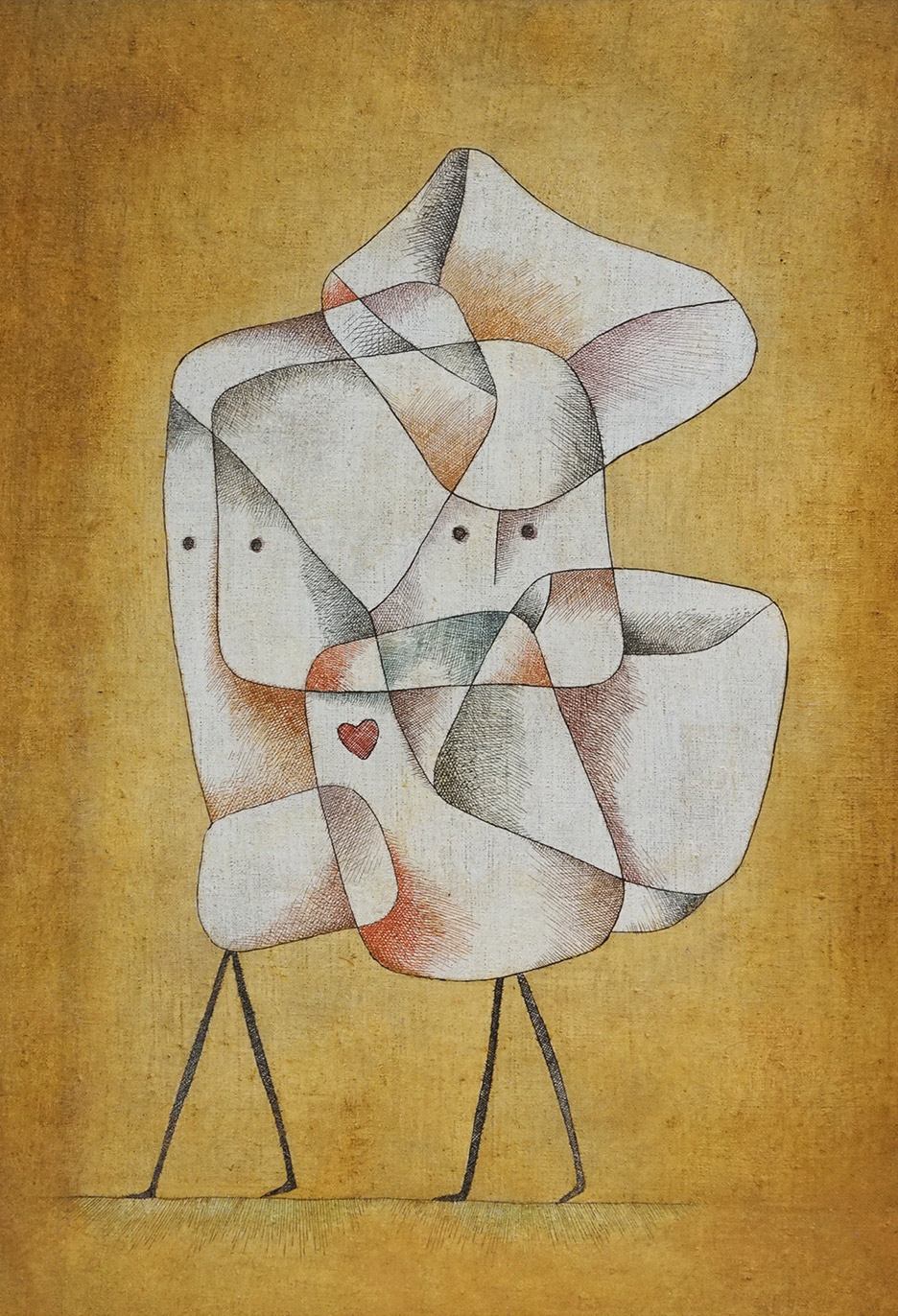

A beautiful Klee watercolour called Siblings from 1930, quirkily and imaginatively, in a way only Klee can, makes us consider the bonds of kinship. On a soft yellow background, a benign two-legged and two-faced creature, birdlike and cloudlike, an amalgam of two people who feel close to each other, shows a single pretty mouth to the world in the shape of a heart, but looks at it with two pairs of eyes.

Munch’s effortless landscape self-portrait with barely suggested facial features from 1904 exudes resignation and quiet confidence. I wish National Portrait Gallery could have secured it for its recent Munch portraits exhibition which was lacking his best self-portraits.

It is always reassuring when a collection has a sense of humour. Jean Dubuffet’s large Minerva from 1945 stares at the viewer, takes over the field of vision with its size, earthy shine and at the same time ridiculous and endearing lack of self-awareness. I like my goddesses to be of this kind. The prankster Michelangelo Pistoletto could always be counted on to provide a humorous challenge. Nurse and girl from 1933 shows two women holding each other up, shown from the back, painted on a large mirror. It is impossible to look at it without seeing yourself in some part of it. The two women endearingly remind me of elderly relatives on a special day out.

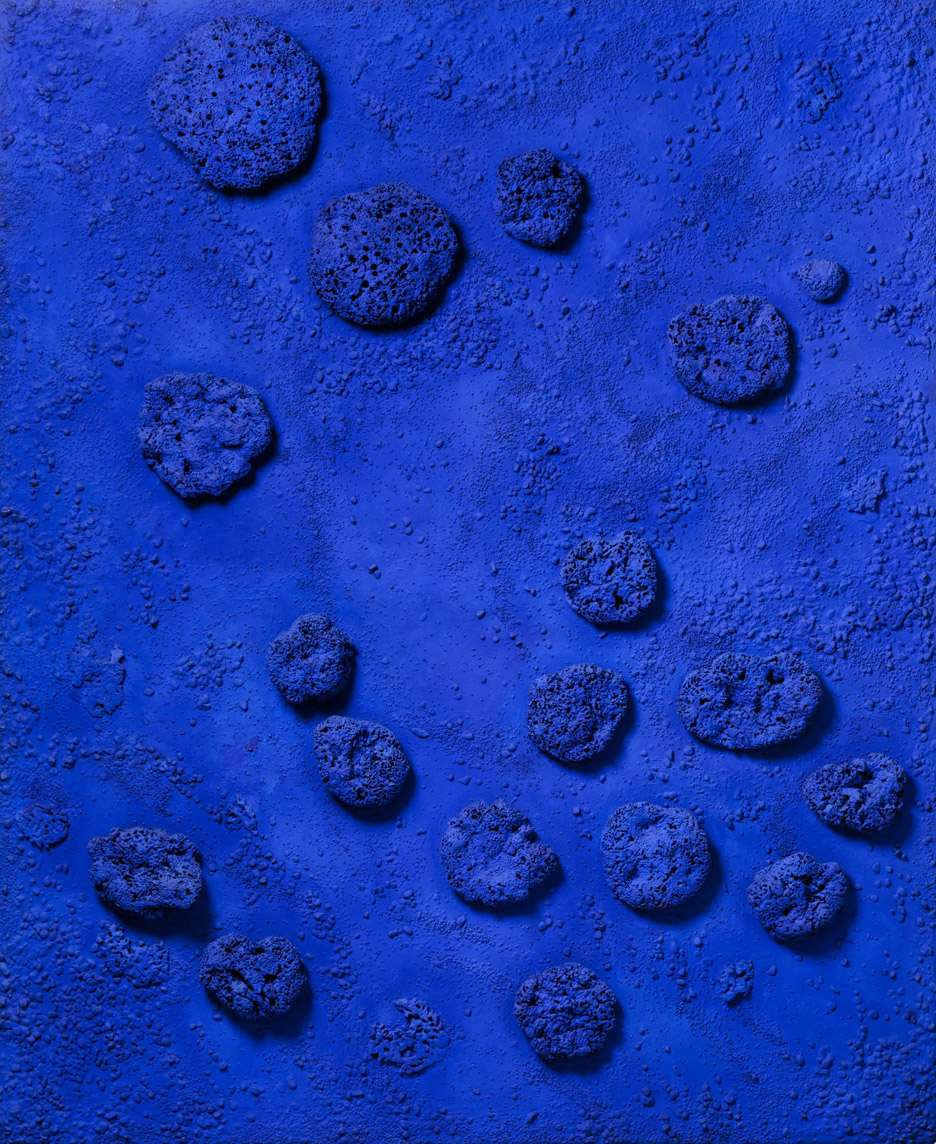

There’s a marvellous smaller radiant Rothko and a beautiful pastoral Franz Marc. Yves Klein’s RE 1 (Relief éponge bleu) from 1958 presents the bottom of the ocean vertically in his patented colour. It is a beautiful and striking piece.

Entitled Experiment Expressionism: Schiele meets Nosferatu, the temporary exhibition unfortunately lacks both a serious approach to curation and bar a few exceptions, good quality works. The attempt to connect Austrian and German expressionists and the expressionist and horror film making in the early part of the 20th century fails as the argument is hardly made either verbally or by juxtaposition of works. The selection of works is puzzling at times and subtopics incongruous. Schiele’s focus on hands can’t seriously be paralleled with Nosferatu. Creepiness they have in common is not an aesthetic. Nevertheless there are a few works worthy of attention hiding in unexpected places.

On the ground floor next to the end of the permanent collection, a few walls are taken up by the museum’s statement regarding the suspicious provenance of some of its collection, considered to have been appropriated under duress from its Jewish owners by Helmut Horten, Heidi Horten’s first husband, during Nazism. The statement is hilarious in that it attempts to be transparent and wash its hands at the same time. Some PR minds must have been working hard to come up with it. The insincerity of the statement which falsely reads as if it’s been made by an impartial party, tries to distract with apparent well-meaning openness, but without really stating anything about the intentions of the collection’s owner to remedy the situation. I cannot honestly decide which is more pathetic, the hypocrisy of the owners or that of the public opinion where this kind of statement is thought of as satisfactory.

It is difficult to brush aside an issue like this, but the excellence of the works in the permanent collection speaks for itself. Ultimately in the democracies we live in, our assent to the rich remaining rich, and the bullies remaining bullies regardless of how they got there, has been bought in exchange for, among other things, publicly accessible art. Panem et circenses. And in the absence of any chance of a more egalitarian meritocracy, let’s at least have more publicly accessible art.