Book

I don’t care

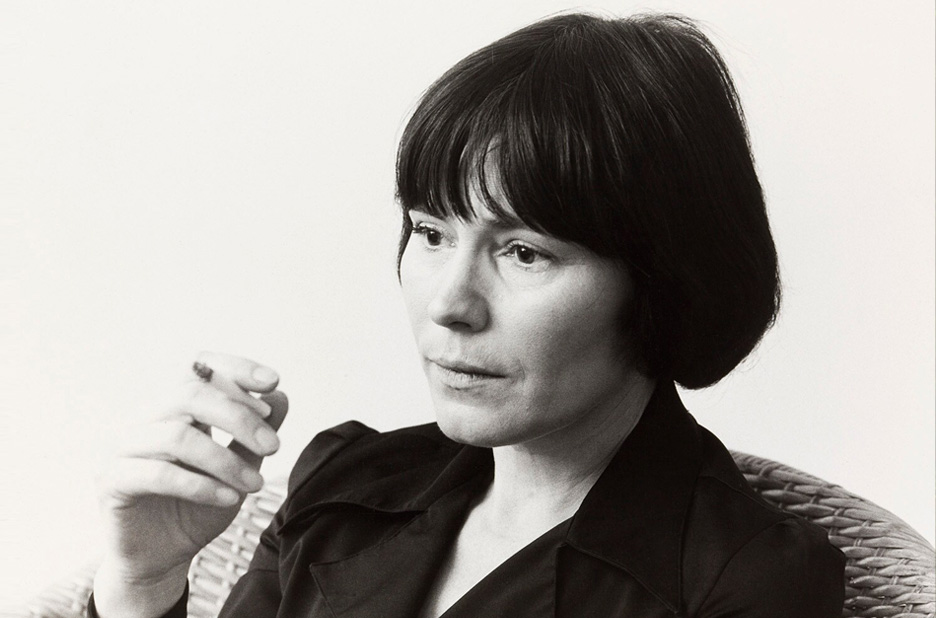

Agota Kristof

4/5

No consolation

Originally published in French in 2005, C’est égal finally gets its English publication in 2025 as I don’t care. This slim volume of very brief short stories contains the essence of the themes which have preoccupied Agota Kristof throughout her literary career. Perhaps they could be summed up as an inexplicable amalgam of attraction and repulsion provoked by the thoughts of home, family and the chosen/inevitable way to live. The intense instinctual desire to get away is tempered by an equally intense yearning for the familiar, and vice versa.

The shorter stories are like poetry in prose, the longer ones have a more substantial twist at the end. The writing is arid and minimal, in the Kristof’s usual style, denying any possibility of sentimentality except in cases when the chilling narrative can overpower it. Just when you think the well-worn ancestral groove has won, Kristof turns everything upside down. Equally just when you think the desire for freedom comes out on top, there is a twist taking us back to the start. Kristof seems to believe that we cannot drag ourselves very far away from the dear and dreaded beginning and this is reflected in her literary structures. The start is all and contains all the possibilities which are then gradually dissipated and lost.

Orphanhood, incest, obsession with home, fascination with houses, with writing, these are all habitual themes in Kristof’s work. There are stories about the plight of wives, mute and subservient, who eventually react. One story My sister Line, my brother Lanoé is about incest, another of Kristof’s persistent themes. A couple of longer stories, my favourites, question our expectations around what we consider to be ‘home’.

The House talks about the human betrayal of a house when moving out. As in Kristof’s trilogy, at the end the boy and old man meet, looking for life in opposite directions.

At home (Chez moi) is perhaps the heart of the collection. It expresses a longing for something to long for and at the same time attempts to identify the meaning of home. This prose poem, a worthy modern descendent of Beaudelaire, is the most serene item in the collection, and it lifts us to a position where we can attempt to observe the arc of life from a safe place.

Some of these stories are about what makes us take a certain radical decision, what leads us to drastically alter our path. It’s usually something very minor, seemingly innocuous, that is the trigger for the long-gestating need for change to take over. In The mailbox an orphan waits for 30 years for any relative to make himself known in writing, which is of course the proper way. When his father miraculously makes contact by letter, the excellent prospects are too much and make the orphan flee far away. The expectations of the father cannot be faulted, it is the orphan’s expectations that are unrealistic. Or is it that we think we want something until it materialises and then we realise we never actually did.

Agota Kristof is quite a unique writer. Apart from carrying a name that makes people smile in disbelief at first because it sounds like a spoof on the name of Agatha Christie, Kristof’s literary wisdom is a one-off. As an immigrant from Hungary who settled in Switzerland and started writing late in life in French as her adopted tongue, first plays, then short stories and novels, she is one of those writers who speak sparingly about the things that really matter. There is no decoration to her texts, they are skeletal and hard, melancholic and instinctively insightful. They delve deep until they reach the last nugget of meaning which cannot be unpicked and then sit on it. Her most famous novel, The Notebook, the first part of her Twins trilogy, draws the reader in with an unusual understanding of a troubled childhood hidden under an apparent anodyne simplicity of writing.

In her short stories which have been reordered for the English release, she is even more reluctant to please. In French C’est égal means ‘It’s the same’ as well as meaning ‘It makes no difference’ hence it is difficult to translate it so that the depressed resignation remains audible. ‘I don’t care’ makes me think of shallow stroppy teenagers and suggests that Kristof doesn’t care, that she is able to let it all slide which is not at all in her personality as a writer. I would have opted for ‘It’s all the same’ which would tie neatly into Kristof’s recurring themes of twinhood and doubling.

Chris Andrews has a tough job here as the translator, because Kristof’s deceptively simple and plain French does not always translate to simple and plain English. Banality and poetry crop up both in English and French, but in different places and to a different effect. Perhaps you could say it is the same difference. The English version seems to me more fluid in places than French, but then simplicity generally reads better in the English language. However, this means that the hard inflexibility of the French is sometimes lost.

I feel I owe a debt to Kristof for understanding that a female writer can also be completely uncompromising like male writers. There is no consolation in her writing, although every so often there is a minute hard-edged trace of enforced serenity – like a prisoner’s violent inscription of his initials on the wall of his cell with a blunt tool.

I don’t care is translated by Chris Andrews