Book

Scattered all over the earth

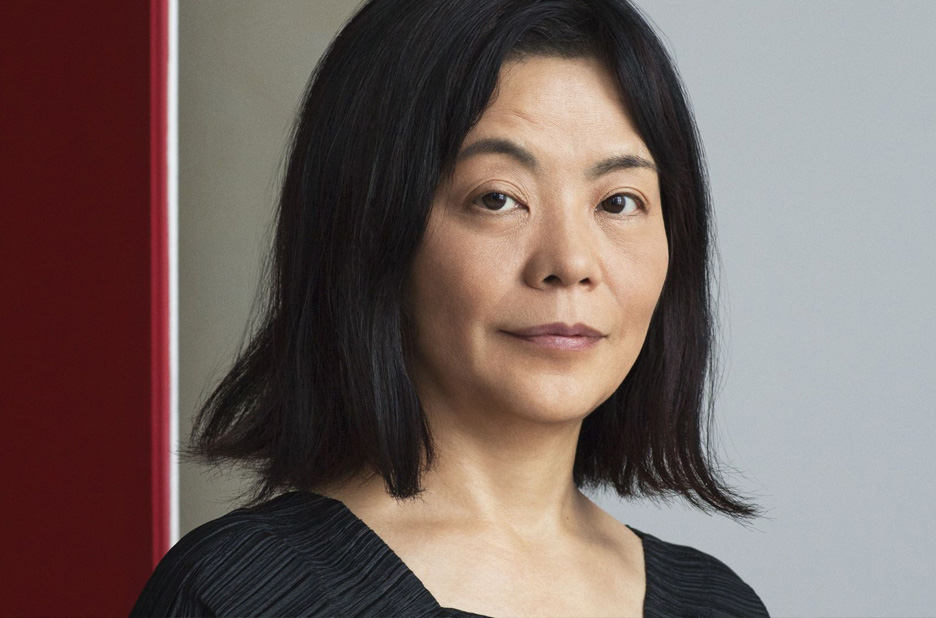

Yoko Tawada

4/5

Non-native speaker utopia

Following the path taken by the main character, Hiruko, an immigrant living in Copenhagen, who collects a motley crew of multicultural travelling companions in her search for a fellow-Japanese speaker, Yoko Tawada gives us an unusual and funny work which defies categorisation. Each of the ten chapters presents matters from a different character’s point of view, but regardless of who speaks the tone oscillates, sometimes with mixed success, indiscriminately combining banality, quirkiness, depth and humour. The final chapter is a tour de force where everything comes together and the true identity of the group is confirmed against the claustrophobic small-mindedness and narcissism they reject. The novel as a whole is also a rich commentary on linguistic and cultural realities, in particular in relation to the immigrant experience.

The action takes place in Europe, sometime in the near future, and there are elements of speculative fiction to the approach, but this does not detract from the narrative which is realistic for the most part. The main premise is that Hiruko’s country no longer exists. We assume this is Japan, but Tawada avoids naming it, calling it the land of sushi instead. There is an interesting element of estrangement that Hiruko obviously feels towards her home country in this refusal to name it, but it also represents a resignation to the lack of interest and understanding of those around her. Nobody seems to know how or why Japan disappeared, although it is inferred this may be to do with the rising sea levels. This spurs Hiruko on to seek others who speak her native tongue. At the same time she finds her home and confidence in Panska, a pan-Scandinavian language she invents that can easily be understood across the Scandinavian countries, is portable when she needs to move, but equally, clearly signals her foreignness.

Coming from Yoko Tawada, a Japanese writer who lives in Germany and sometimes writes in German, the spirit of the novel is very European and cosmopolitan. There is no pretention to this, it is understood as a natural state, particularly for migrants. From Copenhagen where the story begins, the group grows as it travels to Trier in Germany, then Oslo, and finally to Arles in France. It is suggested that they may be on their way to Stockholm next. The unreality of the novel comes from the ease of multicultural existence and communication between the group members, despite clear political, social and personal barriers, and this can be seen as a weakness of the work. But utopias tend to be superficial, discarding complexity to show us a possible different reality. In her utopian enthusiasm, the author even reclaims the name Breivik for one of her minor characters. Ultranationalist and hot-tempered, her Breivik is however law-abiding and ultimately unimportant. I can imagine this narrative as a graphic novel, it has that kind of simplifying characteristic, almost teaching the basics of cultural difference.

There are some hilarious but very plausible swipes at the USA, still without a proper healthcare system, where migrants who speak English are sent by force. Californians are migrating to Mexico for the jobs and USA no longer has the skills to produce basic goods for itself. The English is also mocked as a language polluted by the righteous but false guarantee of democracy.

Tawada has a witty and quirky style which is enjoyable to read. Humour is mostly derived from cultural practices. For instance a restaurant menu in Copenhagen specifies with a number of stars the degree of pain the species felt when it was killed. Danish linguist Knut ironizes: ‘Now that human rights are totally protected, we’re moving on to animal rights.’ But there is also the hilarity of cross-cultural perceptions, which are often also projections, such as when the transgender Indian character Akash describes Hiruko’s appearance as resembling an anime character, cute yet slightly creepy. And of course the misappropriation of food and food references in general are always a fertile source of cultural comedy and Tawada uses this to great effect.

Hiruko’s search is unsuccessful. The first potential Japanese speaker, Nanook, ends up being a fraud, and the second, Susanoo, suffers from aphasia. But this does not deter Hiruko who finds ways to communicate with both of them and to appreciate them for who they are.

Inexplicably Japanese writers seem to often resort to sexual perversions as proof of character and here we have an example of this with the Japanese character Susanoo. But fortunately other qualities of this book outweigh this misstep.

Just by learning another language you get another identity thrown in for free. Nanook, who is from Greenland ends up passing himself as Japanese, because he wants to assume a second identity. He enjoys ‘being misidentified’ and thus escaping assumptions of others. Anyone who speaks another language well knows how joyful and liberating it is to temporarily outplay the stereotype.

Linguistic remarks abound and create interest and humour. ‘I’m not a Buddhist. I’m a linguist.’ says Hiruko. My favourite polyglot joke in the novel is that nothing makes a fight seem sillier than having to translate something in the middle of it. It’s worth remembering this in the moments of red mist.

In the final chapter we witness a showdown between Knut and his controlling mother. Verbally adroit and aggressive and yet handled with an unusual sense of glee, this confrontation and its resolution gives the reader a great sense of satisfaction. Knut’s mother symbolises in part the domineering mother tongue demanding full subjugation. On this emancipative linguistic journey which is set to continue, Tawada proves that the whole idea of ‘native speaker’ and ‘mother tongue’ is a rather childish myth – and there is nothing there to disagree with.

Scattered all over the earth is translated by Margaret Mitsutani