Art

Vanessa Bell

MK Gallery, Milton Keynes

4/5

Playful versatility

It is difficult separating Vanessa Bell’s art and its creativity from her privilege and yet her works enchant with their freedom and playfulness and succeed in taking us to her singular world.

I’ve been meaning to visit the MK Gallery for a while. Their reputation for organising serious and interesting exhibitions has been growing since re-opening in a new building in 2019 and the Bell exhibition aptly subtitled: ‘A world of Form and Colour’ did not disappoint. The beautiful modern building gives plentiful space and light to this surprisingly large exhibition showcasing the wide range of Bell’s work: paintings of course, but also ceramics, book jackets, interior design objects.

Bell must have painted hundreds of still lives and interiors, with or without flowers, and is perhaps at her best in spontaneous playful pieces, such as the vases of flowers decorating Duncan Grant’s bedroom door at Charleston (1918), or the magnificent large Vase and Flowers (1929) from Southampton City Art Gallery. In a similar vein, the joyful Decorative panel with flowers and goldfish from a private collection with the circular pond in the centre, uses flat perspective, a combination of geometric and organic shapes, and unusual colour combinations to create a stunning world of its own, Pompeian in feel, deceptively simple and yet richly rewarding. Some of the more studied compositions can also impress, such as the two canvases from private collections, the Cézannesque grey-toned Still Life with Bottle of Beer from 1913, where the orange triangle on the bottle label anchors the image off-centre, or the late Still Life with a Bowl of Medlars from 1953, more rustic and realistic, the glimpse of the table at the top and the bottom of the canvas skilfully questioning the perspective.

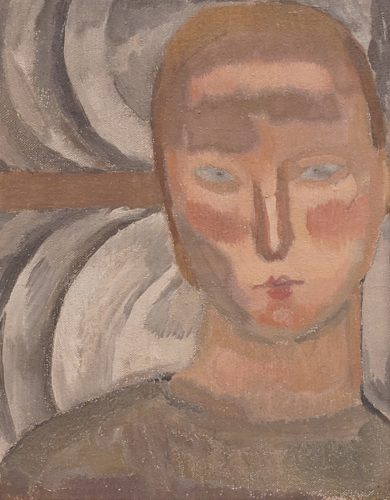

The image chosen for the exhibition material, Study of a Woman from c. 1917, a small canvas of a woman’s head, likely that of Mary Hutchinson, in front of what looks like a kitchen dresser full of white plates, provides an intriguing composition suggesting a multitude of ambiguous meanings. Although in a flat perspective, the woman is not just part of the interior but has her own wilful although mysterious character. The unusual shadows on her forehead and cheek from an unknown source contribute to the impression of her hidden but strong personality. Her mood is difficult to guess, it could be angry, resentful or sullen, or simply tight-lipped and restrained. Her piercing blue eyes are trained on the painter. The shelf of the kitchen dresser parallel with the woman’s eyes implies obscure aggressive feelings of the painter, but equally with the plates and the shadows on the face echoes the forms of Byzantine saints and rulers as immortalised in mosaics. In 1912 Bell and Grant visited the sixth-century mosaics at the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna in which the Empress Theodora is the central figure and subsequently both painted versions of Theodora. The influence of Byzantine and early Christian art can be seen across many works. Study of a Woman visualises the complexities of women’s lives, queens and martyrs, but also kitchen slaves, wilful, but often forced to hide it.

It is said Bell is neglected, but when comparing her to her contemporaries, Laura Knight and Gwen John in particular, I must conclude that she is a less accomplished painter, less fluid and more rambling, although her modern stylistic explorations can make her look more interesting to contemporary eyes. I am conflicted about Bell because sometimes her work appears as if painted by a 21st-century mother of two with no art training and a penchant for the sentimental. Having said that reproductions of her work sometimes don’t do her justice, as once you lose the visibility of the brush stroke, and the luminosity of the colours, the subject matter and the approach can appear banal. Perhaps it is more fruitful comparing her to Gabrielle Münter, another excellent although superior contemporary who also came from a privileged background and whose association with Kandinsky may have saved her from oblivion, in a similar way that the Bloomsbury group helped Bell get recognition which may have eluded a less fortunate woman painter. Some of the conversation pieces are reminiscent of Münter. The best known of them, A conversation (1913-16) from the Courtauld, stages an intimate huddle between three women in front of a window with the bright garden flowers in the background. The focus is on the natural movement of the woman on the left talking, confiding perhaps in the other two who listen intently. The atmosphere is engrossing, but the technique rough and clumsy in places. The curators mention Matisse’s The Conversation (1908-12) as inspiration, and perhaps this is also the connecting piece with Münter, but I am also reminded of collaborating women in Artemisia Gentileschi’s heroic canvases. The composition is set with the grey curtains parting and surrounding the figures conspiratorially. As her sister Virginia Woolf reflected in A room of one’s own, it is rare to see a representation of female friendship in art: “Almost without exception they are shown in their relation to men. (…) And how small a part of a woman’s life is that.” With a freer brush years later The Garden Room at Charleston from 1950 continues the conversation showing generations of women in easy companionship with a luminous garden as a backdrop.

The star exhibit has to be the Famous Women Dinner Service (1932-34), 50 Wedgewood ceramic plates hand-painted by Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, exhibited for the first time in a gallery. I have only previously seen photographs of it and it was joyful admiring the real thing in front of me. Again it’s the playfulness of these plates that wins the observer’s affection. Bell and Grant include themselves in the set, humorously making Grant the only man included. We don’t know who painted which plate or how the arrangement of the plates was decided on. Bell’s representation of herself is typically humble and low-key (or is it Grant’s representation of Bell?). The personalities include queens, writers, artists, actresses and beauties. Virginia Woolf is included of course in a flattering if bland youthful portrait. Every plate is different and unique, down to the decoration of the rim. Blues and browns dominate with occasional golden or russet accents. From Lady Murasaki who penned The Tale of the Genji, to Miss 1933, each woman has an equal place in the set and can also stand as a work of art on her own. Bell played down the feminist implications of this work, but certainly enjoyed visualising these women and representing their various expressions of strength.