Book

I will never see the world again

Ahmet Altan

5/5

Poetry of resistance

This little gem of prison literature can only be described as a lesson in resilience. Altan not only strives to see poetry in everything, he also actively puts in practice methods of preserving and shielding his spirit from the crushing reality of prison. And his strategies are not only smart, they are also beautiful, and superbly translated by Yasemin Çongar.

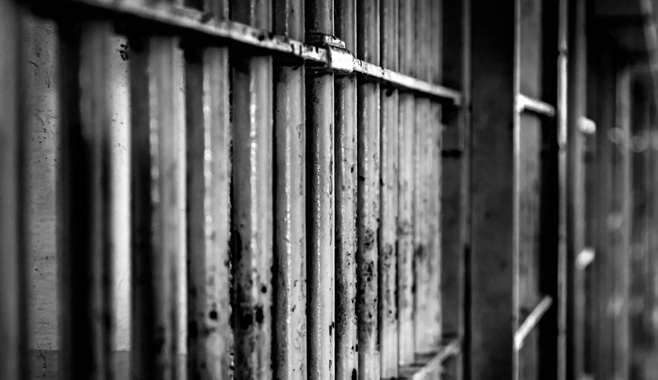

Imprisoned by the Erdogan regime for some imaginary crimes, Altan knows that he must submit. He has been expecting the police to arrive any day at the crack of dawn and has a small bag ready for such an occasion.

The first two chapters are just the most extraordinary. In simple language imbued with the knowledge and calm philosophical acceptance of facts, Altan tells us how he was arrested on a peaceful September morning together with his brother who lives in the same building.

He experiences a déjà-vu, as one of the events which marked his childhood was seeing his father arrested in a similar fashion, forty-five years previously. Then he waits for the reality to hit him, which he describes as his head hitting the coffin lid. And then comes the key sentence he utters to the policemen when offered a cigarette: “I only smoke when I’m nervous.” This is a masterclass in self-manipulation for the purpose of self-protection. Of course he is nervous but denying it in this way can only help him resist, however briefly.

“That single sentence suddenly changed everything.

It divided reality in two, like a Samurai sword that in a single movement cuts through a silk scarf thrown up in the air.”

Altan analyses the elegance of this simple intuitive and unpremeditated solution to his predicament which makes a part of him feel untouchable. Mental resistance is key to stopping him from sinking any deeper than he cannot avoid. Changing the reality through the power of imagination, a writer’s gift, is an extremely useful talent in prison.

“I took a deep breath to push my lungs back down.” he says talking about the moment we all know well when we try to keep ourselves together in the face of overwhelming obstacles. Keeping yourself together is vital in prison, Altan tells us, since by giving in to the all-pervading despair only once could mean losing everything and being unable to come back. With compact sentences containing only the essence he describes the physical effects of anxiety and panic, and the way in which we humans try to countenance it.

It is well known that when we hit rock bottom the thought that we would die has a calming effect. In his beautiful limpid poetic prose Altan describes how in those moments the thought of our insignificance removes the unnecessary pressures we feel daily as human beings to behave in accordance with our own high standards.

There is such a wealth of perfect poetic moments in this book, the only way to describe them is to quote them: “I will survive by hanging on to the branches of my own mind, at the very edge of abyss.”

In the chapter ‘The Teacher’ Altan retells the moving story of one of his prison inmates through his poetic lens. The teacher spent the happiest years of his life living humbly in a remote Kurdish village and teaching in the village school. Altan wants to understand at what point the teacher made the decision to stay in the village, when was the exact turning point in his life. It must be the moment, Altan concludes, when he decided to walk on foot the last part of the journey to the village in a snowstorm. He walked for hours, getting lost several times. When he finally made it to the village, he had made the decision to stay. “Becoming a snowflake had such a delicious, burning zest to it”, writes Altan, “a sense of bleeding and breaking as if one was giving birth to one’s new self.”

The teacher only talks about his time in the village as if nothing else before or after matters. Altan appropriates the moment of the teacher’s decision, when he stepped out of the minibus in the snow. The delight of holding onto someone else’s little key to happiness in moments of high despair. The teacher held fast in prison, perhaps leaning on his memories of happiness, and didn’t give the torturers any names.

Some of the people Altan encounters in prison are deeply religious. Some of those are open to the conversation about religion and others not. Some of them are humane and other not. Not that religion or lack of it is a sign of humanity, but an ability to be open to others certainly is. The only way to retaliate against those who are closed to others, Altan decides, would be to treat them as a topic of research.

Things of course get harder as time moves on. It becomes more difficult to extract poetry and beauty from the wretched reality of prison, when even time won’t cooperate and continue to pass.

“To review certain books seems like an impertinence.” writes Simon Callow at the start of his review of this book in the Guardian. And indeed writing about such a special book threatens to diminish its glow. How can other words possibly add anything to it?

Altan was arrested in 2016. He was sentenced to life without parole in 2018. He was released from prison in 2021 having spent 4 years and 7 months in Silivri prison outside Istanbul. After several appeals and two retrials, in 2024 Altan was sentenced to 6 years, 3 months and 18 days in prison. Then another appeal process began. He currently lives at home in the Asian part of Istanbul and is not allowed to leave the country.

I Will Never See the World Again is translated by Yasemin Çongar