Film

The Limits of control (2009)

Jim Jarmusch

5/5

Reality is arbitrary: the road of abstract retribution

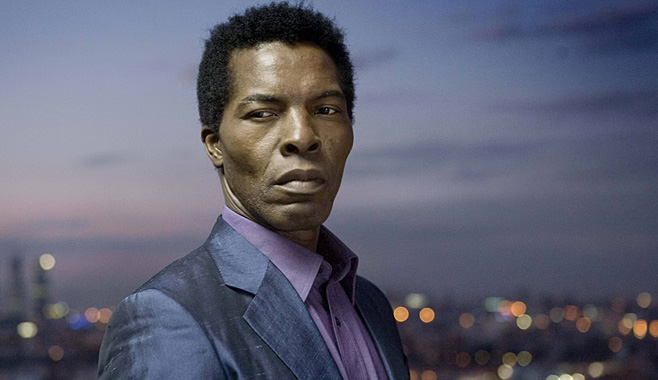

The Limits of control is one of the most underrated films by Jim Jarmusch. It’s frequently dismissed as shallow and self-indulgent, and yet there is so much to it. The story centres on a nameless hit man, played by a Jarmusch regular, Isaach de Bankolé, who takes an elaborate journey in Spain to kill his target. It’s the journey itself that counts as in all Jarmusch films and with typical irony this film about a hit contains minimal violence. Reminiscent of Ghost Dog, Jarmusch’s earlier hitman road movie with Forest Whitaker, the highly disciplined ascetic lifestyle of the hitman contains unusual rituals: morning tai chi sessions in an elegant suit and always ordering two espressos at the same time, to name but two.

A hitman whose job it is to wait and observe is an ideal subject through whose eyes we can see the world, cities, people and artworks. Paintings, photographs and objects are juxtaposed with their subject in what seems a meditative celebration of the search for understanding and developing imagination.

The journey is punctuated with meetings with a string of international characters who offer information, often in a language the hitman doesn’t understand, about the next step of the journey. Jarmusch rejects the Hollywood monolingual and monocultural film culture and his films frequently include several languages and cultures in its script, location, cast, music and cultural references. Seemingly understanding someone who speaks in an unknown language is a motif that Jarmusch uses to a great insightful and humorous effect as he has done before in Ghost Dog.

Each conversation with these handlers takes the same form. “¿Usted no habla español, verdad?” (“You don’t speak Spanish do you?”) is the initial password after which the handler launches into an interesting but unrelated personal monologue on life and art. At some point matchboxes are exchanged containing a small piece of paper which we assume contains the actual information relating to the hit. The hitman swallows the piece of paper after reading with one of his two espressos.

Every time I watch this film I notice something different. The last matchbox message for instance, blank for the first time, is like a little origami mirroring the sparse mountains.

The journey from Paris to Madrid, then Seville and finally Doña Maria is not only beautiful and stylish, in large part due to Chris Doyle’s stunning cinematography, but also meditative, full of artistic references, parallels and insights. For instance the little railway station at Doña Maria-Ocaña in a landscape similar to the American South-West is a famous western shooting location.

This is a rare if not the only film where Jarmusch takes a semblance of a political stance. He seems to be at pains to make it as abstract as possible, to hide it inside the deadpan narrative, but it still stands out with an unusual clarity. The chosen victim of our hired killer, played by Bill Murray, an arrogant, bad-mouthed and aggressive man in a suit, can only be a representative of the American late capitalist political system. The crass banality of this man stands in stark contrast to the meticulous self-contained discipline of the killer and the cultural sophistication of the network who aid him. The killer is like an abstract thought made flesh confronting the very physical example of a seemingly limitless power embodied by the target.

In Seville we are treated to a flamenco rehearsal sequence. Featuring a full live music performance has become another regular theme in Jarmusch’s films and it’s the rare moment when we see the hitman smiling in enjoyment. It is another type of ritual of course and he is familiar with those. “El que se tenda por grande” which is performed, a source for another set of repetitions and echoes, provides a key statement of the film: “He who thinks he is bigger than the rest must go to the cemetery, there he will see what life really is. It is a handful of dirt, a handful of dust…”

The presence of humour in Jarmusch films is very much underappreciated. The deadpan storytelling is often funny in its juxtaposition of simple actions and their confrontation with the reality or perception which Jarmusch’s zombie movie The dead don’t die takes to a career high. There is the simple almost slapstick humour in the hitman’s polished routines and the threat of their pointlessness, and also more complex irony of an agent of American power being strangled with a string from a venerable Manuel el Sevillano guitar, representing a culture he loathes.

We never see how the hitman enters the target’s highly-guarded compound in the middle of nowhere. He allegedly used his imagination. The Limits of control is really a film of culture versus violence. How can we deal with the violence of the modern world? The answer could be – with ritual, patience, observation, imagination, art and the occasional organised hit.