Book

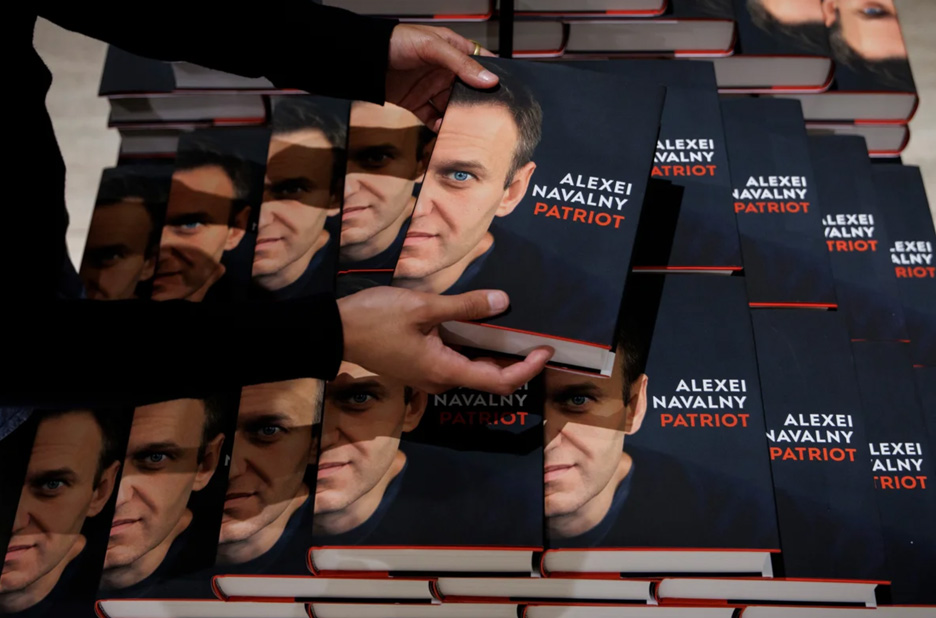

Patriot

Alexei Navalny

5/5

Russia will be happy!

I didn’t think reading this book would make me respect Navalny, his resilience, bravery and commitment, any more than I already did, but it has done exactly that. Discovering all the details of his fight against Putin’s dictatorship, I am in owe of the persistence and positive energy of this man who inspired many Russians to support him in his fight for a better Russia. Furthermore I have also learnt that he was highly erudite, a great reader, very funny, curious and open-minded and with an engaging writing style.

Many accept that Navalny was the most credible political challenger to Putin. Had he prevailed, and eventually perhaps became president or elected politician, Navalny would probably have become a nationalist and it is likely that he may have displayed some undemocratic tendencies. Mother Russia has such a long history of gobbling up all resistance to autocracy that it is almost impossible to imagine that this could change substantially. But Navalny didn’t prevail. He was martyred by the Putin’s regime and as such will be remembered as one of the brightest lights of the opposition. Putin’s calculations have held, but I do think he has misjudged the meaning of martyrdom in a country where the Orthodox Christianity is increasingly dominant. Although today the spineless Russian Orthodox Church aligns with Putin’s rule and conquests, things can easily change. One day there will be large city squares and space stations named after Navalny. He may even be declared a saint.

I was interested in this memoir to get insight into the intriguing character of Navalny. In trying to pinpoint what is special about his personality which facilitated his development into such a formidable political activist with incredible resilience, I could identify two aspects. First, he admits that he was always a joker which landed him in trouble since his school days. He seemed to get a kick out of riling the representatives of the system and it appears that he could emotionally experience this as an end in itself. Pranking government officials is a national pastime in Russia, at least lower ranking ones and for those with little to lose, but Navalny takes this to a whole new level. In a jaw-dropping moment in Daniel Roher’s Oscar-winning documentary about the investigation into Navalny’s poisoning he elicits an explanation over the phone of how he was poisoned. He is impersonating an FSB agent, and in the memoir you get the idea how this was possible for a son of a soldier, brought up in an army town, who understood first-hand how the military superiors talk to their underlings. Second, he was completely intellectually relentless in questioning absurdity and endless lies which made him a good lawyer and also fed into his humour. These two sides of him, the joker and the interrogator, had allowed him to be satisfied with small gains in this monumental fight against a much stronger adversary, and to keep going.

By entitling his memoir ‘patriot’ Navalny uses an ambiguous and complex word to define himself. Straight away it signals to the reader that everything he has done was for the benefit of his country, Russia, but ‘patriot’ does have some negative connotations as well. Those who currently claim this word in the most vocal and chest-beating ways in the West tend to be despicable extreme right-wing hypocrites, so it is difficult to take this term without feeling some irony. But I think Navalny means it in earnest and as a way of sending one last taunt to Putin.

Regarding the charge of nationalism, Navalny is evasive. This is perhaps the only topic where his intelligent thought-through approach fails him or he simply doesn’t want to elaborate so as not to alienate his readers. Which is fine, as there are plenty more important topics that this book covers. The gist of his answer is still very positive: he believes in talking to everyone and doesn’t think a serious leader can decide to ignore huge parts of the population because he may personally dislike their views. Perhaps this is a lesson to politicians in the West who are currently having exactly those issues of not knowing how to engage with extreme right nationalists.

The book consists of disparate parts that work very well together. The first few sections are written in Germany while recovering from the Novichok poisoning which took place on 20th August 2020, and they cover the poisoning incident (without repeating what Daniel Roher’s documentary shows) with memorable witty passages about his hallucinations and helplessness while in recovery, and then his background, family and education with interesting insights about the transition years in Russia under Gorbachev and Yeltsin and the general political landscape in Russia. His damning analysis concludes: “A cool, objective look at the Yeltsin era confronts us with a dismal and disagreeable truth, one that explains Putin’s rise to power: there never were any democrats in government in post-Soviet Russia, let alone freedom-championing liberals who opposed conservatives desperate to resuscitate the U.S.S.R. The whole lot of them – with rare exceptions (…) – were an unholy horde of hypocritical thieves and lowlifes.”

Chapter 8 is a turning point, written in prison after returning to Russia on 17th January 2021. Unless the chapters have been reordered, it seems he succeeded in writing another 10 chapters in prison detailing his inspirational fight against corruption in Russia and various attempts to win elections despite severe restrictions and regime interference. The book continues with his prison diary which he kept from his arrest in January 2021 until circa mid-2022. As diary entries become more sparse, sections from his letters are featured instead. Although Navalny stays remarkably upbeat and positive in his diary and letters, slowly, inevitably, under the abusive practices of the Russian prison system, his tone becomes more sombre.

At the end of the book, the editor highlights in the epilogue Navalny’s diary entry from 2022 after his conviction in March. It is a good choice to end the book with this powerful text where Navalny states that he knows he is most likely to die in prison and talks about the two mechanisms of coping which he recommends to those who find themselves in similar circumstances. The first is the complete acceptance of the worst-case scenario, which is not easy to achieve, his ‘prison zen’ as he calls it. The second is religion. Even the most uncompromising atheists, and I include myself in this group, although I admit being in a Russian prison would seriously test my thinking, can see after reading this 500-page book how religion can assist the human spirit in these extreme circumstances to resist the escalating prison treatment intended to break it.

The third technique which he doesn’t mention in this section but gives plentiful examples of throughout the book is humour. In the most unlikely situations and most unexpected moments Navalny writes down hilarious remarks which break any transition into melancholy or sentimentality about the situation he finds himself in. When he is given the strictest punishment in prison of punitive solitary confinement towards the end of the book, he comments: “I feel like a tired rock star on the verge of depression because I’ve reached the top of the charts and there’s nothing more to strive for.”

Whoever reads this book won’t have a single doubt that Putin killed Navalny. The intensification of humiliation, restriction and isolation throughout the period of his incarceration from 2021 until his death this year on 16th February 2024 demonstrates clear intent. Stalin and other dictators present and past have proved many times that a penal system can be used with impunity on a huge scale to simply slowly wear down your opponents until they are crushed mentally and physically, but to read a personal account of it makes you feel the injustice and the simple waste of human potential much more acutely.

Throughout the book there are brief but tender mentions of his family who have steadily supported him. His brother Oleg spent 3 years in prison on trumped-up charges as part of Putin’s retaliation, but never complained and urged his brother to continue: “Don’t stop! If you were to stop, it would mean that I’m in here for nothing.” His wife Yulia who edited his memoir was his strongest supporter. They had a great relationship, and together accepted and prepared for the likely occurrence of him dying in prison. The psychology of a political activist’s wife deserves separate attention and we will have to wait and see whether Yulia Navalnaya rises to prominence as a political activist continuing the good fight.

The book also includes several powerful ‘final words’ that Navalny is allowed to make during his many court cases. The one I appreciated the most is the speech at the Yves Rocher trial where he builds on a theme of all those complicit with the regime who are staring at the table:

“Why do you put up with these lies? Why do you just stare at the table? I’m sorry if I’m dragging you into a philosophical discussion, but life’s too short to simply stare down at the table. (…) The only moments in our lives that count for anything are those when we do the right thing, when we don’t have to look down at the table but can raise our heads and look each other in the eye. Nothing else matters.”

This outstanding and moving account of an extraordinary life devoted to one’s country is not only an insightful and satisfying read but also inspiring and needed in our fractured age. Navalny’s life story and his thinking should be known and disseminated in the hope that one day Russia will indeed be free and happy as he predicted, hopefully in our lifetime.

Patriot is translated by Arch Tait and Stephen Dalziel