Film

The Seed of the Sacred Fig (2024)

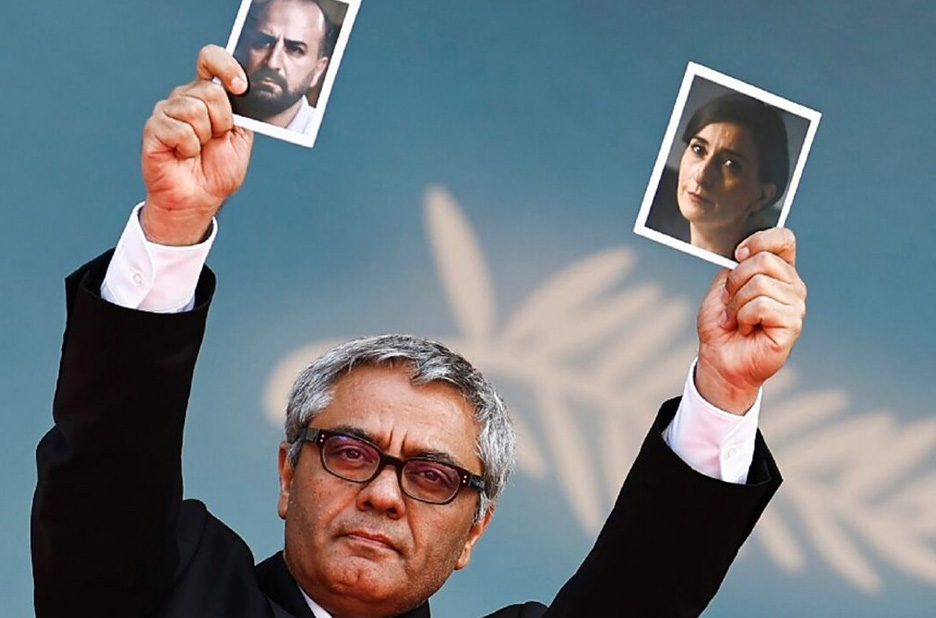

Mohammad Rasoulof

4/5

The naked truth of extreme Islamic ideology

This brutal, uncomfortable and unsubtle film holds the mirror to the murderous and misogynous regime and gives no respite to the audience from a claustrophobic reality with no exit.

In complete contrast to another excellent Iranian film which came out last year, My favourite cake, which devastated viewers with sensitivity, The Seed of the Sacred Fig takes no prisoners in making a strong political statement about the rotten core of the regime’s ideology. Both films focus on realities of life under the Islamic dictatorship but take a completely different approach.

Knowing that the director Mohammad Rasoulof has been imprisoned for his work, has had to escape Iran and has filmed this work in secret and remotely, helps to put things into perspective. Otherwise this film is in danger of appearing unpalatably brutal. It is a story of an Iranian family under increasing pressure to conform beyond all reason due to the head of the family having been promoted to an even more brutal – but respectable in this upside-down world – position of investigating judge to the revolutionary court in Tehran.

The first scene sees him leaving the courts dismayed and walking past the cardboard cutouts of officials with their hands on their chest in the traditional gesture of unconditional love and acceptance of God and his alleged will, which is in fact shaped only by fanatical blinkered men. The metaphor of the cardboard cutouts is probably the most subtle moment in the film.

The family consists of the promoted father Iman, his submissive wife Najmeh and two daughters, 21-year-old Rezvan and teenage Sana. To a western woman’s eyes the wife’s conformity appears unreasonable and uncomfortable, but at the end of the film it is clear that it is due to sheer self-preservation. The two daughters challenge the status quo, initially mostly softly and tentatively. They struggle to reconcile what their intelligence concludes with what they see around them. The claustrophobic atmosphere in the household gradually intensifies.

Iman inhabits the monstrous logic of the regime until his very last breath, starting as a seemingly sensible person and escalating rapidly into treating his family not only as enemies of the state, but his own enemies that is his God-given duty and right to crush. He simply cannot act any differently. With Iman’s character Rasoulof shows the full application of this extreme ideology. ‘How far would you go’ is no longer a hypothetical question, it is encoded in this ideology’s fundamental beliefs that the answer is ‘to the bitter end’, with no space for pity or mercy let alone simple humanity. The result is the desired wilful annihilation of two generations of women. Fortunately the daughters rebel, first challenging the regime’s nonsense as spouted by their father and in the conclusion of the film by desperately fighting for their very lives.

The acting is excellent. The two daughters in particular played by Mahsa Rostami and Setareh Maleki show the strength of their characters in sometimes unexpected ways. The three young actresses playing the daughters and their friend were forced to flee Iran after taking part in this film. Soheila Golestani who plays the mother has been arrested. The film and reality are very closely interlinked.

To her father’s rhetorical question “Don’t you think I know best having worked for the courts for twenty years?”, the elder daughter says “No, you are part of the system.” This exchange feels like a small vindication as it occurs after many uncomfortable minutes witnessing the women’s distress. It’s the younger daughter however, who you may have thought may not be mature enough to form a considered opinion, who gets to show her grit in the final scenes. The only hope Rasoulof tells us is with the younger generation. The final scene suggests that stomping the ground sufficiently hard in protest may perhaps lead to the collapse of the entire ancient, ugly and rotten edifice.

“My cinematic language was initially very metaphorical,” says Rasoulof. “I believed metaphors helped me navigate the limitations, but eventually I realised I was just aiding the censorship. I wanted to be true to myself. After my arrest in 2010, I told myself, ‘You’re a film-maker: do what you want, don’t hold back.’”

I can’t say that I recommend the viewing of this film. It is simply crushing. And I feel it is more depressing for women in the audience because the depicted victims are again women. Innocent, ordinary, intelligent women who don’t ask for much but to live with a bit of dignity. And their situation is entirely hopeless. Nevertheless this is an important political film about the depths of depravity of the Iranian state. For Iranians this is not just a film, it’s a matter of life and death.