Art

Bonnard and Japan

Caumont Centre d’Art, Aix-en-Provence

4/5

Ukiyo-e lessons in modernity

Set in the beautifully restored 18th century mansion Hôtel de Caumont, the exhibition Bonnard and Japan shows off the strong influence of Japanese ukiyo-e prints on Bonnard’s painting. Each room displays a mix of Japanese prints and Bonnard’s work on a similar subject and invites visitors to make connections. It’s always a pleasure seeing Bonnard work or the Japanese woodcuts, but having them side by side in the same exhibition, even without drawing comparisons, is a happiness-inducing combo.

Anyone who has seen Bonnard’s last self-portrait from 1945 (Fondation Bemberg, Toulouse), unfortunately not featured at this exhibition, can see the extent to which Bonnard was influenced by Japanese art. It looks like a humble portrait of an aging Japanese man in a kimono. As in many of his paintings, facial features are painted as unimportant echoing the ukiyo-e facial stereotypes.

Bonnard owned a substantial collection of Japanese prints, a few of which are also on show. This ‘very Japanese Nabi’ adopted many Japanese composition techniques such as a photograph-like cutting-off of subjects placed at the edge of the canvas which gave his paintings a modern dynamic quality. He also incorporated bright colours, flatness of perspective and colour, empty flat space alternating with filled space following the Japanese aesthetic which shifts the balance of his compositions, providing a stylised harmonious whole, hinting at things not pictured and allowing the observer to use his imagination. But his interest in Japanese art also extended beyond the techniques to adopting the aesthetic of the prints, perpetuating the ukiyo-e spirit in his otherwise very French art.

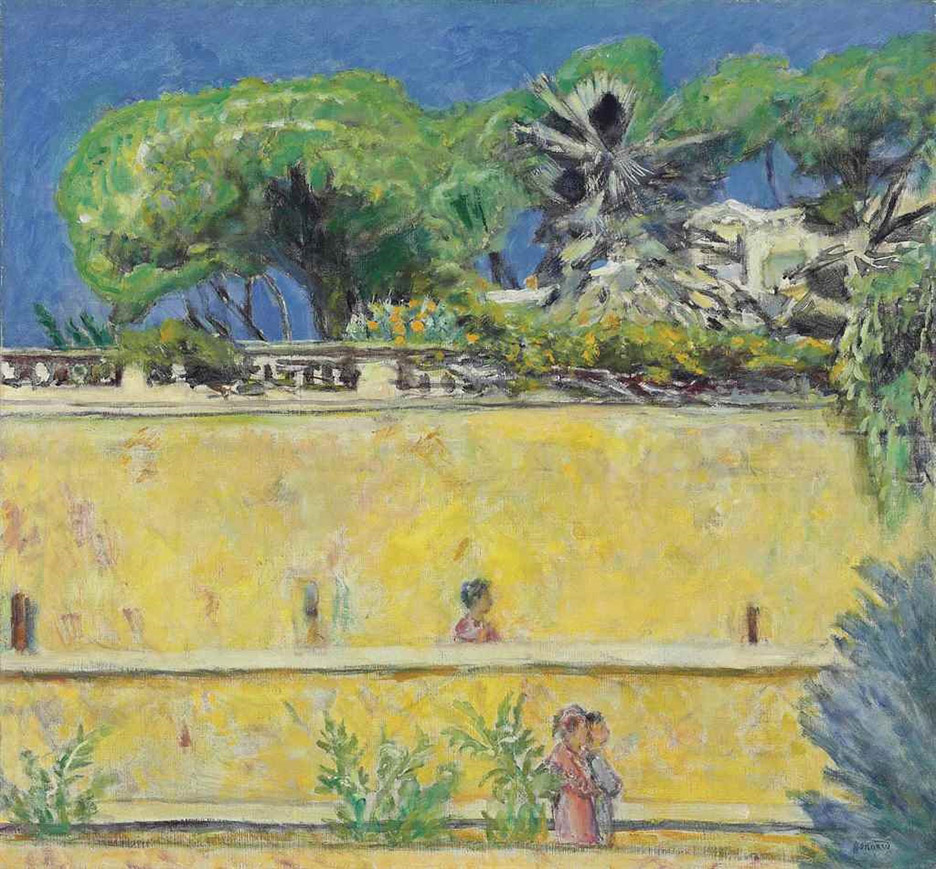

In Terrasse dans le Midi (c. 1925) a blue tree is cut-off on the right, but its contribution to the composition cannot be overstated. Loosely painted figures in profile, plants and windows punctuate the flat sunny surface of a beautiful yellow. The Japanese print composition techniques are transplanted into the hot South of France where they create a meditative and modern photographic canvas suggesting much more than they show.

Another fascinating exhibit is Bonnard’s design for a cupboard decorated with stylised playing dogs (Groupe de chien dansant, projet de meuble, 1891, private collection). It is excessive art-nouveau and yet the stylisation is also oriental in its sinuous lines, flatness and complementary contrast between the paired animals, the whole reminiscent of Van Gogh who was equally influenced by Japanese prints. It appears as if Bonnard adapted another painting in the exhibition of two dogs playing (incidentally a loan from Southampton gallery) to furniture design. In contrast to the cupboard’s exuberance, in another small painting of a dog from a private collection (Un chien, c. 1890), the painter’s frequently painted dachshund dozes while a few gentle brush strokes suggest colourful plants in the opposite corner. The restrained approach and gentle palette convey the warmth of an everyday scene.

Several nudes are shown at the exhibition, two of which particularly stand out. One of them very vertical, the other very horizontal. The vertical nude, Nu gris de profil (c. 1933), is surprisingly showy and sensual, but the accent is as always with Bonnard on a wonderful composition grouping the long straight body with the blue mosaic floor tiles, a small rectangle portion of turquoise and golden yellow sun showing through horizontal gaps in the closed shutters. The predominantly blue-grey and golden hues depict the handsome effects of sunlight. Reprising the motif seen in several of his canvases, the horizontal nude lies in the bath submerged in water (Nu dans la baignoire, 1940). The crop is tight resulting in an almost abstract painting of vertical blue-grey lines. It could be a picture of depression or melancholy, or simply another stunning composition.

The exhibition successfully shows that Bonnard’s adoption of the Japanese aesthetic was not a passing fascination. He permanently altered his artistic vision by absorbing these influences into his own authentic style. Japanese influence is not always obvious or explicit, but it consistently points the way to modernism.

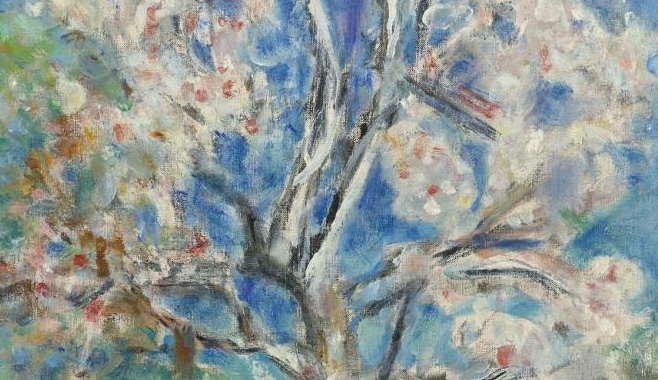

The star of the show is the painting of the treasured almond tree in Bonnard’s garden, L’amandier en fleurs from c. 1930. The first tree to blossom at the end of winter, it reportedly gave him strength to paint it every year. The luminosity of the puffy clumps of white flowers serenely and joyfully dominate the bright colours. Although smaller than expected, the expectations having been set by the glorious large exhibition posters, the painting radiates Hanami spirit.