Art

Maria Helena Vieira da Silva

Guggenheim, Bilbao

5/5

Unique urban abstractions

When I first discovered Vieira da Silva’s work, I wondered how it is possible that she is not better known. The Guggenheim exhibition first in Venice and now in Bilbao may help spread the word about this exceptional artist. The museum building in Bilbao, one of the most successful of Frank Gehry’s creations, is an ideal setting for Viera da Silva’s architectural abstractions which are equally playful and intricate, and display a comparably rich personal understanding of space.

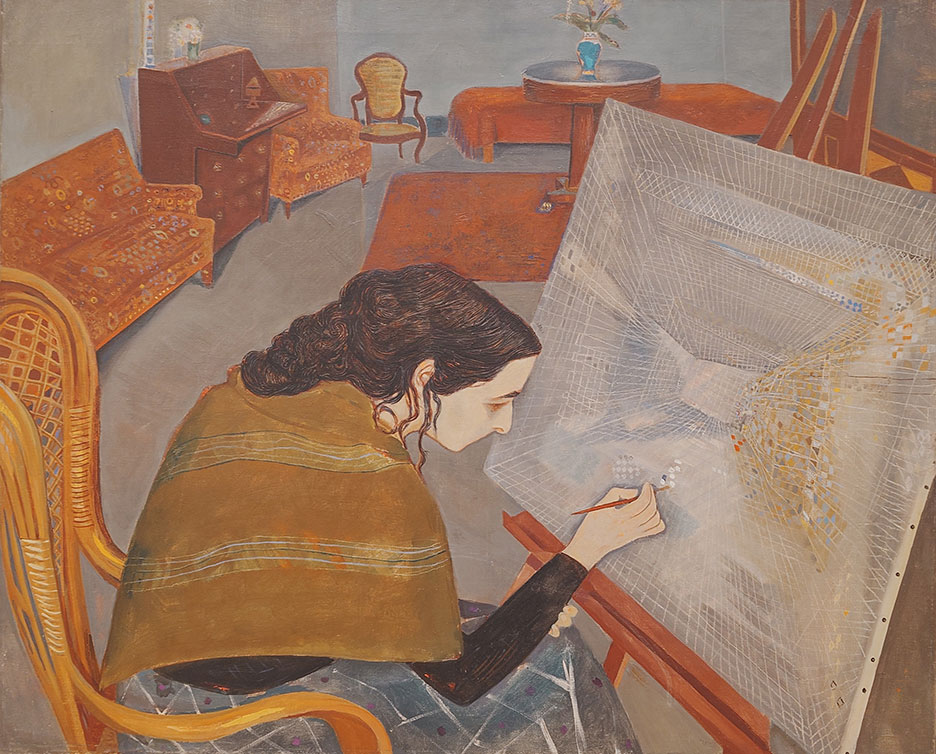

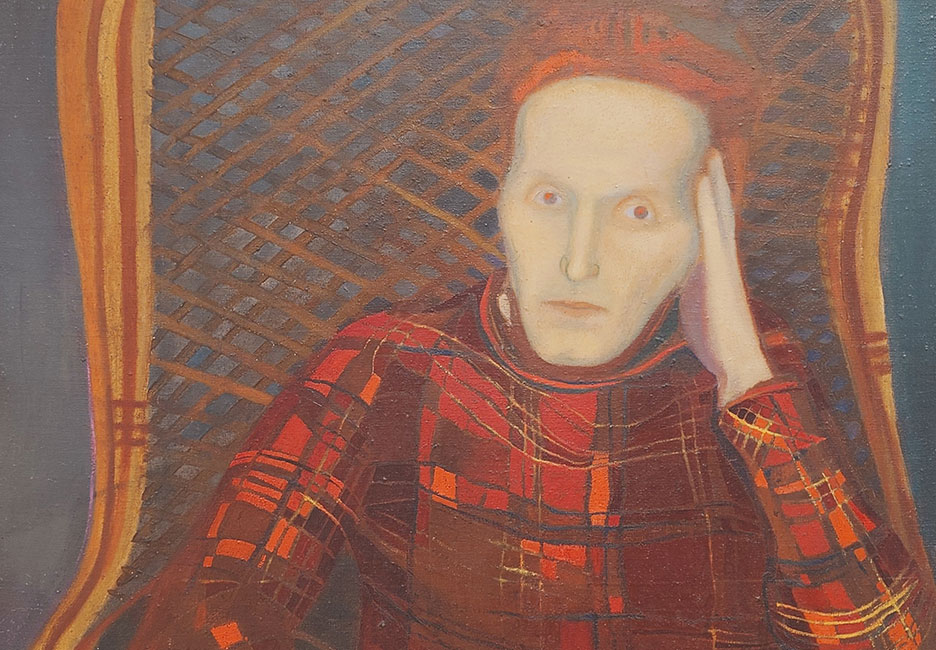

The first canvas on show is a portrait of Viera da Silva by her husband Árpád Szenes. The subject is protectively surrounded by the warm browns of wooden furniture while she paints her idiosyncratic tiles. She appears like a little girl lost in play and this is an image that stays with me throughout the exhibition. Vieira da Silva portrays her husband in turn like a fascinating wizard, in a red tile patterned top, with flaming red hair which extends into the wicker chair cane. This intriguing couple of equals supported each other’s work throughout their lives.

Viera da Silva was a woman of the city, instinctively multicultural and regardless of where she found herself she saw the cityscape with the same benevolent creative eyes. The mood of her paintings is predominantly cerebrally playful, akin to Klee, conferring the artist’s enjoyment of the visual ramifications of her work. On the rare occasion that the painter descends into the more explicit misery of life, this is coupled with the appearance of fully formed figures. But it is her abstractions that win the argument with their positive statements on the nature of space.

The characteristic motifs of her work are rectangular organic tiles, modified by perspective, and sometimes further split into triangles, modern in their simplicity but seemingly inspired by the azulejos of her native Lisbon, paving complex spaces which could be simply interpreted as fields of vision or internal corridors of the mind. These spaces often deepen in the middle to show more of themselves to the viewer constrained by the same human field of vision and instinctively intent on moving forward. The underground from 1948 is a typical example of this approach, surprisingly unclaustrophobic although fully enclosed, like an imaginary tunnel of the London tube, but in contrast a captivating magical location, an alternative land of wonders for a modern meticulous Alice.

The veranda from 1948 reprises the same structure although this time its origins in reality are a little clearer. One could visualise this as a reduction of an existing tiled space lit by the sun and reflecting other surfaces. The hallway or the interior also from 1948, another variation, is perhaps the most quietly colourful of all Viera da Silva’s content enclosed spaces. Like a bright vision in the middle of a dull underground car park, it enchants with the unexpected three-dimensional twists.

Every so often these tiled spaces become shape creators themselves and generate hidden rudimentary human figures such as in Ballet figure from 1948 or Red chess board or chess players from 1946. The safe and tamed nature of these locations is confirmed by the dream-like figures which peek out from behind the tiles and fade back into them.

Sometimes the tiles disintegrate into grids and although these may appear less unique and more similar to the explorations of other abstract artists, they gain a suspended lightness and contain developments which attract the eye. The grids sometimes evoke huge libraries such as in the magnificent Maze from 1975. Something different occurs in The bird cage from 1948 which explores the spatial relationship between confinement and freedom. What we see in the cage, which like all self-imposed prisons is partially open, are not recognisable birds but several colourful clumps of feathers, like shadows or reflections of a bird’s fast circular movement around the cage. Perhaps this may just be a cage with a memory of a bird. And if this is so then this painting follows the same pattern seen elsewhere of evoking the spirit of spaces, the feeling of the memory spaces retain of beings and objects who dwelt in them.

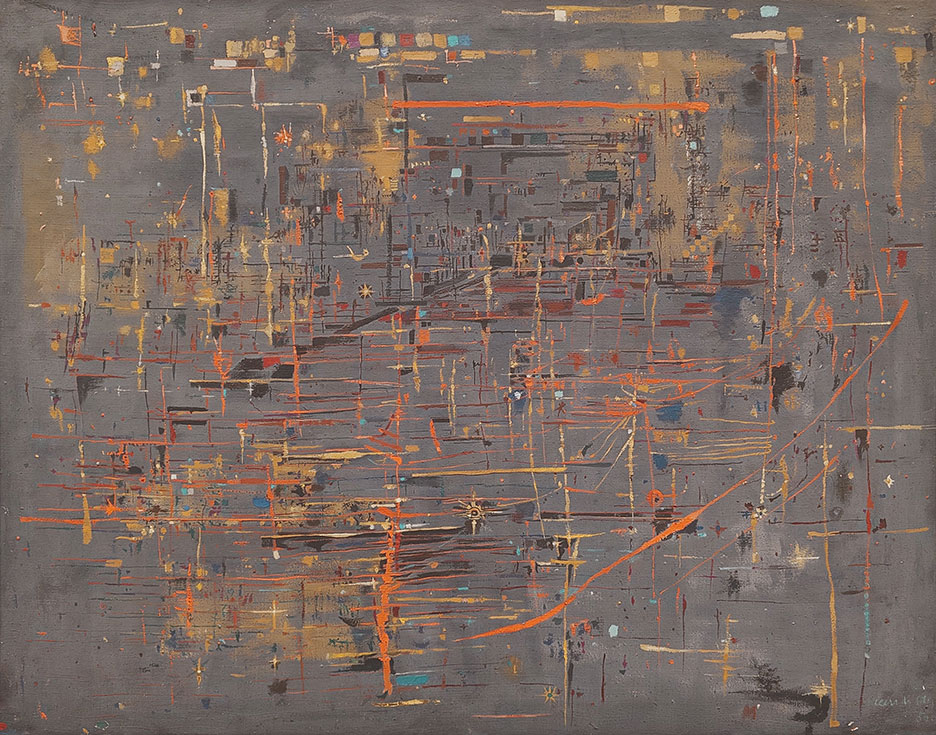

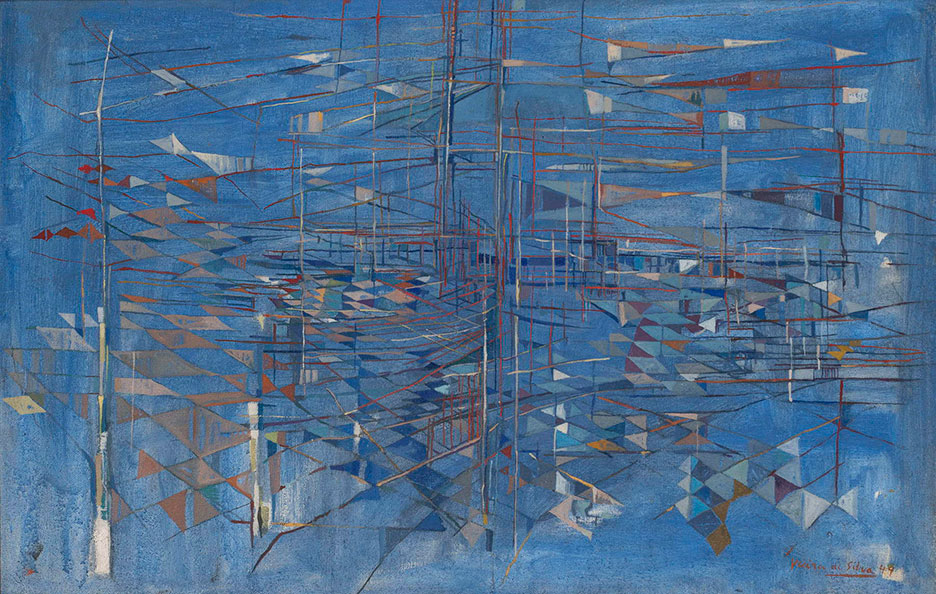

The evolution of these interiors into cityscapes seems inevitable. We are treated to two highly accomplished cityscape abstracts from private collections. The enveloping vision of a city at night in The night city or the lights of the city from 1950 balances warm yellow-orange lights on a dark purple sky. Venetian festival from 1949 puts the ubiquitous tile motif to use again to depict a mixture of Venetian flags and harlequin outfits on a fluid blue background crossed by imaginary masts and poles. The shape of vessels and the movement of water is skilfully suggested in this three-dimensional abstract structure.

The exhibition culminates in the last room where the chronological narrative is broken and works across the painter’s output are selected for their use of the colour white which the painter increasingly turned to in her later years. In this white room a couple of Vieira da Silva’s stunning late works sit across from a few of her most remarkable earlier canvases. Equity from 1966, one of the largest paintings on display continues the theme of an enclosed rectangular space, this time stripped down, exploring the idea of its vertical symmetry. Reminiscent of Albers in its relentless geometrical logic, this development of rectangles is nevertheless created in a very different spirit which eschews Albers’ severity and remains meditatively in the domain of human imperfection. The dialogue from 1984-88 continues this theme, reducing it further and concentrating the intricacy on the furthest side of the space, in the middle of the canvas. It is interesting to contemplate that Viera da Silva completed this painting as she was reaching eighty, still pursuing her path of abstraction.

But let’s rewind to the White composition from 1953 in the same room. Topographical phantasy of a settlement in the middle of a wide snowy landscape or a meditation on the organic purity of bluey white, a study on silence or simply yet another engaging exploration of space, either way standing in front of this painting envelops the viewer in a unique world which breathes wonder and contentment.